In case you missed very interesting discussion on Oct 9th 2023, Grave Matters has asked me to prepare a blog post of my talk! I’m Robyn Lacy, a PhD Candidate in historical archaeology at Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador. My research focuses on 17th-century burial grounds and burial landscape development in the colonial northeast of North America. Part of that research led me down a research hole into the history of coffin and shroud use in early colonial burials, and what the archaeology of these graves can tell us about their construction and use.

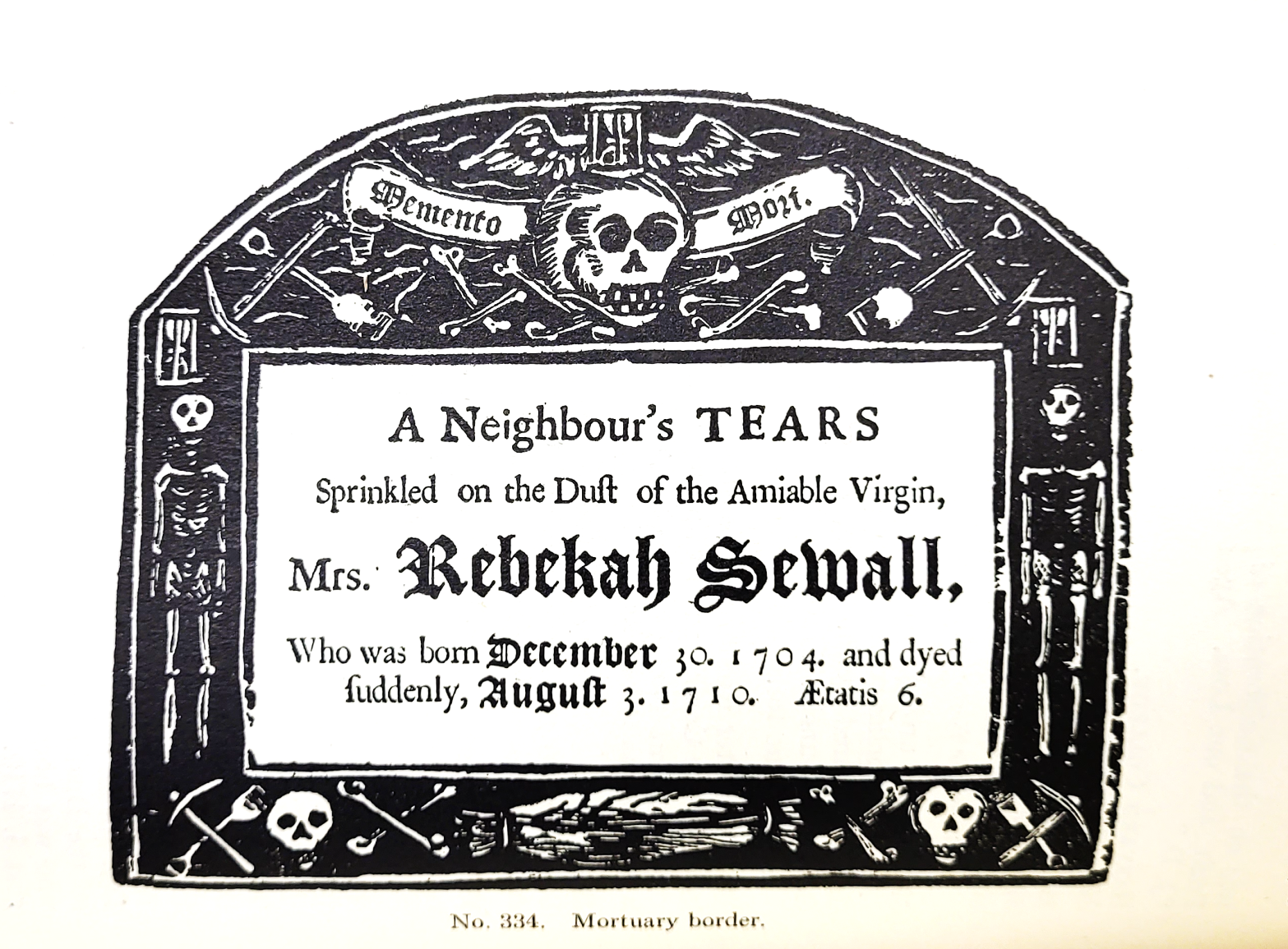

There are many contemporaneous depictions of coffins and shrouds from the 16th to 18th centuries, such as those found amongst the other mortality symbols on funeral tickets advising the community of an upcoming burial. The funeral ticket of Rebekah Sewall, daughter of famous judge and diarist Samuel Sewall of Boston, Massachusetts, shows a skull with a winged hourglass, bones, tools for grave digging, skeletons, and a shrouded body below the text which is tied at the head and feet.

Before coffins became widely used, people in Britain were typically buried in a winding sheet or shroud, secured at the head and feet with a knot or string. If they could not afford their own coffin, they were carried to the grave in a parish coffin, but only buried in their shroud. Even bodies buried within coffins were often wrapped in a shroud, although this was not always the case, and in terms of archaeological evidence, it can be very difficult to determine whether someone was buried in a shroud or not. Clues such as the positioning of the body itself, whether the limbs are tight together or more open is a good indicator of them being secured with a shroud or having the limbs tied tightly together. There have not been many full excavations of 17th century burial grounds in North America, but from the sites that have been excavated, like St. Mary’s City in Maryland and Jamestown Virginia, we are able to get an idea of what settlers were doing in terms of burials in communities of varying religious backgrounds.

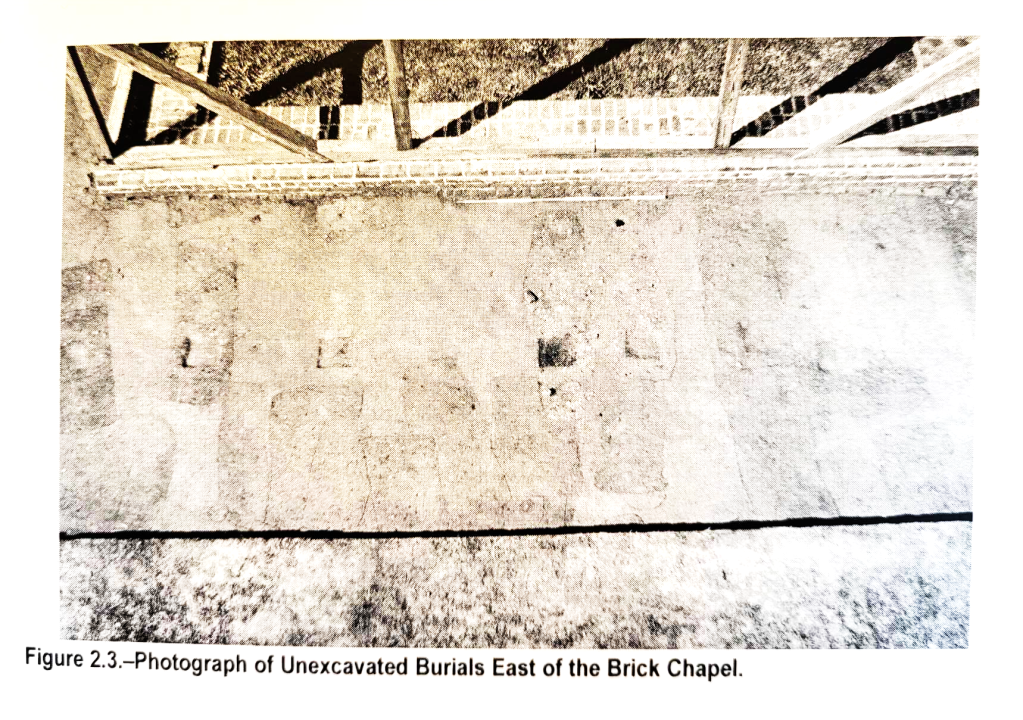

Before we can find out much about how people were buried through archaeology, we have to identify the burials themselves. When a grave is dug, soil is removed and the layers mixed up, and then placed back into the grave shaft, which we’re able to see in the soil. It’s typically a different texture and/or colour than the undisturbed soil around it, which you can see in the photo above! After the grave shaft is identified, the excavation of the burials can begin. You can see some examples of identified grave shafts at St. Mary’s City in the image above.

Coffins were typically rectangular or hexagonal prior to the 17th century, with a flat or gabled lid that was detached from the body of the coffin, although gabled coffin lids are only known in England through contemporaneous illustrations (Llewellyn 1991). There is some archaeological evidence that this shape of coffin lid did exist in North America in the 19th century, through finding rows of nails down the centre of a grave shaft. Another unique coffin shape is the anthropomorphic or ‘anthropoid’ lead coffins, coffins that have a slightly human shape, were also somewhat popular during this period. They were chosen by upper class families who could afford not only an expensive coffin, but often also have a brick or stone family vault (Litten 2009; Mytum 2018:9). These coffins were very popular to those who could afford them in the late medieval period, but we don’t really see them in North America. We do, however, have archaeological examples of anthropoid wood coffins at St. Mary’s City.

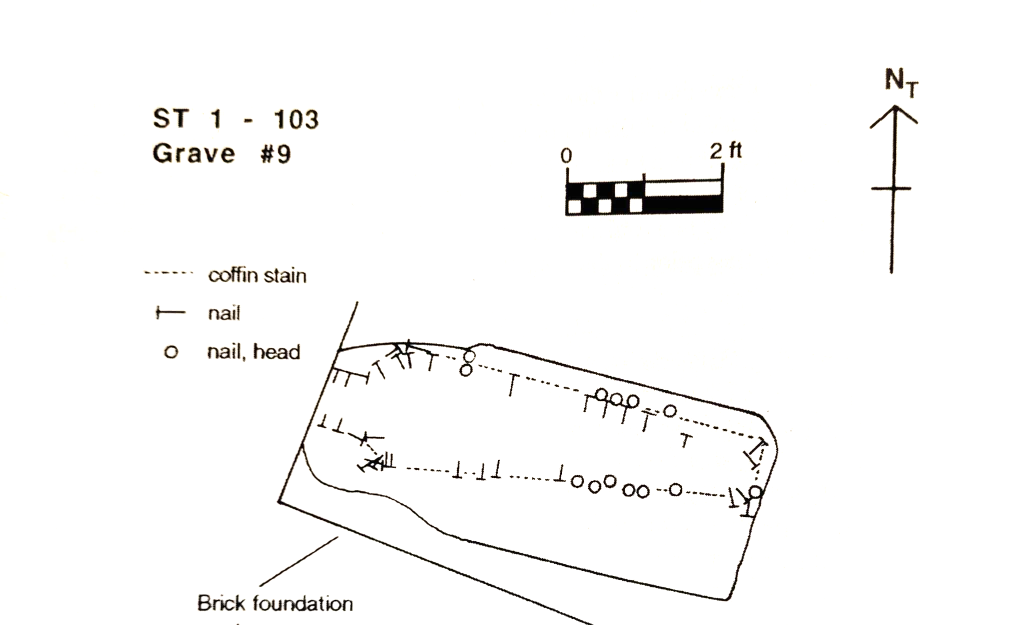

Timothy Riordan indicates that the increased use of coffins through the 17th century can be seen in the colonial Chesapeake through the archaeology, where the use of a coffin becomes almost universal by the end of the 17th century (Riordan 2000:5-1). Shrouded burials without a coffin only appeared in the early period at the site, roughly 1634-1667. This demonstrates that the use of coffins was reflecting roughly the same timeline as in Britain at this time. The image below shows the plan from Grave #9 where you can see the grave shaft as well as the shape of the anthropoid wood coffin. The positioning of the nails at the head and feet gives us an idea of how the coffin was constructed, and the ‘head box’ is clearly visible at the west side of the coffin. St. Mary’s City is also home to five lead coffins which date to the 17th century, the only known examples of lead coffins from this period in North America.

In 2016/2017 I was part of the team excavating a 19th century burial ground in Foxtrap, Newfoundland, that was on industrial property so we exhumed the burials for reburial in a safer location. The property owners contacted the archaeology department to ensure there was no damage to the burial ground from their business, and the burials are going to be reinterred at a local cemetery at a later date. The excavation was the first full excavation of a historic period cemetery in the province so we learned a lot about how people were buried in the late 1800s in an outport (coastal rural) community.

Due to the acidity of the soil in Newfoundland, there was very little organic material left of the burials. Instead of intact coffins, we had soil stains in place of where the wood once was, where the organic material had decomposed in situ and changed the composition of the soil. Based on the variety of nails we saw at this site, the coffins were produced with whatever was on hand, and yet we still see the iconic hexagonal shape being produced.

You can see in the photo of the excavated grave shafts that they were roughly shaped rather than the machine-cut rectangles we are familiar with today, and were aligned approximately east/west. Finally, in the last photo, you can see a copper pin that was recovered from around one of the individual’s heads, with a piece of their hair stuck to it. These are typically called ‘shroud pins’ but were not actually used to close the shroud. Instead, they would have been used to secure a strip of fabric together to hold the jaw closed, or a face covering over the person’s face. The corroding metal actually helped preserve material we might otherwise have lost, like portions of the skull and these delicate pins. If you’re interested in reading more detail about this excavation, you can see my blog post here. It also includes links to the report in the NL Provincial Archaeology Office’s annual review.

There you have it, an introduction to coffins and shrouds in colonial North America. Thank you to Grave Matters for having me speak at their seminar, and if anyone has any questions for me in the future, you can find me on twitter @graveyard_arch or @graveyardarch on Bluesky.

References:

Grimes, Vaughan, Maria Lear, Jessica Munkittrick, and Robyn S. Lacy

2018 Excavation and preliminary analysis of a historical burial ground at Foxtrap-2 (CjAf-10),

Foxtrap, Newfoundland. Provincial Archaeology Office Annual Review, 2017. Provincial Archaeology Office, Department of Tourism, Culture, Industry and Innovation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Available online at: https://www.gov.nl.ca/tcar/files/Vol-16-2017.pdf

Holt, Elizabeth, 1985 The Second Church of Elizabeth City Parish, 1623/4-1698. Archaeological Society of Virginia: Virginia.

Litten, Julian, 1991 The English Way of Death: The Common Funeral Since 1450. Robert Hale: London

Miller, Henry, and Travis G. Parno (editors), 2021 Unearthing St. Mary’s City: Fifty Years of Archaeology at Maryland’s First Capital. University Press of Florida: Gainesville, Florida.

Riordan, Timothy B., 2000 Dig a Grave Both Wide and Deep: An Archaeological Investigation of Mortuary Practices in the 17th-Century Cemetery at St. Mary’s City, Maryland. St. Mary’s City Archaeology Series No. 3. Historic St. Mary’s City, Maryland.