The deathbed is the site of one of life’s most dramatic transitions as friends and family gather round to witness the once vital loved one become a lifeless corpse.

In the mid to late nineteenth-century the urban middle- and upper-classes increasingly had the moment of death overseen by a medical professional, with the body and burial later dealt with by an undertaker. Allan Kellehear calls this a ‘managed death’ and argues that in urban areas the dying became consumers whose dying needs were met by various professionals, their autonomy in the process surrendered.[1]

But for the rural working classes death continued to occur at home. This allowed for a more traditional deathbed scene with friends and family gathered round to say their farewells and ease the passage of the dying. Folkloric rituals passed down through the generations were often performed at this moment of transition, revealing that for the rural working classes some magical thinking persisted.

This blog will examine the evidence from nineteenth-century folklore collections to explore the emotional role of deathbed folklore. I will argue that the ‘altered state’ of the newly-dead represented both a responsibility and a threat to the family, requiring the performance of a variety of comfortingly familiar rituals to ensure the spirit’s safe passage onwards.

The Deathbed

The final moments at a deathbed provide difficult emotional terrain to negotiate. There are inner feelings to process but also an obligation not to upset the dying person or the wider family. Eleanor Hull in her collection of British folklore emphasises the pressure to contain raw emotion:

‘Tears should not be allowed to fall heavily upon the dead, for the dropping of the tears of mourners are felt like heavy weights, hindering the deceased from the rest he needs.’[2]

This requirement for stoicism came from a long tradition – Susan Broomhall discusses how in the early modern period, pregnant women were urged not to allow any strong emotion to be enacted bodily, lest it have a negative effect on the unborn child. This, she argued, placed a ‘moral duty’ on the soon-to-be mother.[3]

This idea of a moral duty can be extended to the deathbed as evidenced by much of the folklore which implies that the living held a certain agency at the moment of death.

Tradition dictated that the family and friends who gathered around the deathbed must not cry too hard or ‘wish’ their loved one to stay too much because this was thought to hold the dying person back, preventing them from passing on. This folkloric tradition and its attendant ‘moral duty’ encouraged the family to emotionally let go of their loved one.

Agency

Folklorist Richard Blakeborough wrote that: ‘Few country people doubt the existence of a power by which the living can (as they put it) hold back dying.’[4]

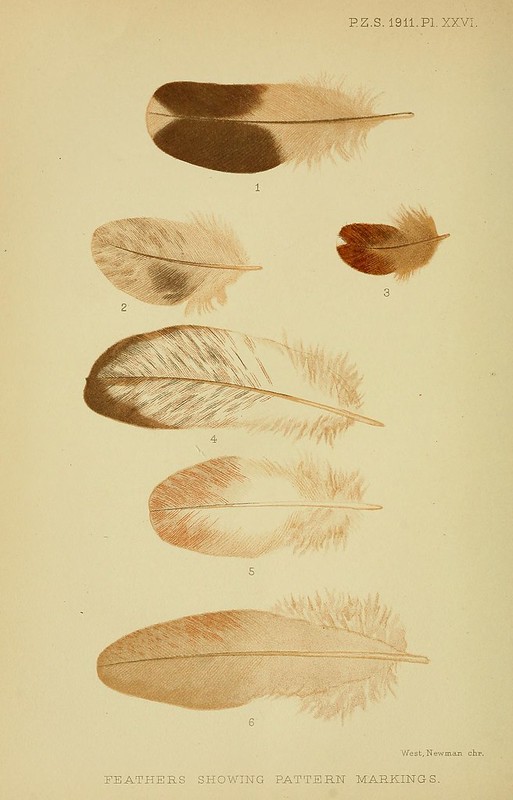

This idea of agency is seen in the widespread belief that a person cannot die if they are lying on a bed containing feathers (most commonly pigeon feathers, but hen or game feathers are also mentioned). Many of the folklorists record that if it was suspected that there may be pigeon feathers somewhere in the bed, the family would move the dying person to another bed or chair, with many reporting that death soon followed, seemingly proving the effect of the feathers in holding a person back.[5]

I have yet to find any explanation as to why pigeon feathers were thought to hold a person back from death, the meaning presumably having been forgotten. But I have been thinking that perhaps the link comes from the homing nature of pigeons. Pigeons are domestic birds with a strong instinct to return home and this could explain why the feathers were thought to tether a person to home.

Despite the loss of meaning, the belief that death could be hastened and eased by moving the dying away from a bed containing pigeon feathers persisted. I contend that this was because it puts some power and agency back into the hands of the seemingly helpless relatives; allowing them to focus their emotional turmoil onto a positive, and familiar, action.

This piece of folklore could work both ways. Blakeborough goes on to report that: ‘Instances are on record of pigeon feathers having been placed in a small bag, and thrust under dying persons to hold them back, until the arrival of some loved one; but the meeting having taken place, the feathers were withdrawn, and death allowed to enter.’[6]

The deathbed is a site of uncertainty and torment. It can be agonising for the family to watch their loved one slowly fade away. The idea that death might be paused or hastened by the movement of a bag of feathers would have given the family a genuine feeling of power and agency over the moment of death.

The Lingering Spirit

Belief has pervaded since prehistoric times that the newly dead may linger near their body.[7] The liminal status of the corpse invites the still living to perform rituals that might help them pass unfettered to the other side, such as the custom of opening a window to allow the soul to depart.[8]

It was customary for the family to refrain from doing anything which might prevent the upwards flight of the soul. As a result doors and windows were flung open to remove any barrier for the departing spirit.

This implies belief in the existence of an ethereal spirit that exits the body at the moment of death and travels on to the afterlife. It’s interesting to note that ghosts were often depicted as able to travel through solid objects and yet this folkloric belief suggests that the spirit could be blocked by a closed window or door.

Opening windows and doors is another example of a ritual which can be performed at the moment of death, almost embodying the act of letting a loved one go by physically making the route clear. This is an active rather than a passive tradition, the physical performance of the folklore giving a bodily outlet for emotions and allowing mourners to focus their grief onto a positive action.

The Spirit Passing On

The traditional belief in the lingering soul could also be an uncomfortable one, leading some to worry that the dead might be envious of the still living and return to haunt them.

This anxiety motivated some of the other folkloric practices at the moment of death, for example the extinguishing of fires[9]. By deliberately putting the fire out the family were symbolising that the deathbed was no longer a comfortable, warm place to remain.

The performative aspect of these cultural practices also reveals the perceived threat represented by the corpse. Death signals the end of the physical life and the transition of the spirit into the afterlife. The spirit once untethered from its earthly body is transformed into something which, if trapped on earth, could become menacing. This implies that the only safe and proper place for a person’s spirit after death was the afterlife, it was not desirable for the spirit to linger, its journey must not be obstructed.

To this end mirrors were covered because it was believed that the spirit could become trapped inside its reflective surface.[10] And some families would remain silent for a few minutes after death to ensure the spirit was not distracted from its onward journey. This reflects the belief that uttering someone’s name is a summoning act which could call back a departing spirit and result in it failing to move on.

Many of these folkloric acts are reminiscent of protective magic. This suggests that the purpose of deathbed folklore was not limited to assisting the loved ones’ spirit in their journey onwards but it also played a role for the remaining family, acting as form of protection for the still-living who feared the lingering spirit.

Conclusion:

Folklore was not a generic practice but varied from region to region, family to family. However the evidence collected by nineteenth-century folklorists provides some common themes which reveal aspects of rural working-class death culture and allow some insight into the emotional role and function of traditional death folklore.

The traditions passed down through generations may have in some cases lost their meaning over time, but the continuing performance of familiar customs would have evoked a sense of community and kinship for the gathered family.

The performance of deathbed folklore wordlessly communicated care and compassion for their loved one in their final moments; gave the family some feeling of agency in the transition of their loved ones’ spirit from this world to the next; protected the family from future hauntings; and showed the wider community that the dead had been afforded a traditional, and therefore a respectable, send-off.

Claire Cock-Starkey is a second year part-time PhD student at Birkbeck University of London. Her project examines the folklore of death and dying in nineteenth-century England. Claire is also co-convener of Grave Matters: A Death Studies Discussion Group.

[1] Allan Kellehear, A Social History of Dying, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2007, p.7.

[2] Eleanor Hull, Folklore of the British Isles, Methuen, London, 1928, p.210.

[3] Susan Broomhall, ‘Beholding Suffering and Providing Care: Emotional Performances on the Death of Poor Children in Sixteenth-Century French Institutions’ in K. Barclay et al eds Death, Emotion and Childhood in Premodern Europe, Palgrave Studies in the History of Childhood, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57199-1_4, 2016, p.69.

[4] Blakeborough, Richard, Wit, Character, Folklore and Customs of the North Riding of Yorkshire, Henry Frowde, London, 1898, p.119.

[5] Sidney Oldall Addy, Household Tales with other Traditional Remains Collected in the Counties of York, Lincoln, Derby, and Nottingham, London, 1895, p.123, Blakeborough, p.120, Morris, p.59.

[6] Blakeborough, p.120.

[7] Plinio Prioreschi, A History of Human Responses to Death: Mythologies, Rituals, and Ethics, Edwin Millen Press, Lewiston, 1990, p.203.

[8] John Nicholson, The Folk Lore of East Yorkshire, London, 1890, p.5.

[9] Blakeborough, p.122.

[10] Denham, p.77.