The Victorian language of flowers spoke not only to the affairs of lovers, but to universal human concerns about life stages and remembrance of the departed. In this blog post, follow examples of nineteenth-century floriography that contemplate transience, memento mori and the possibility of second flowerings.

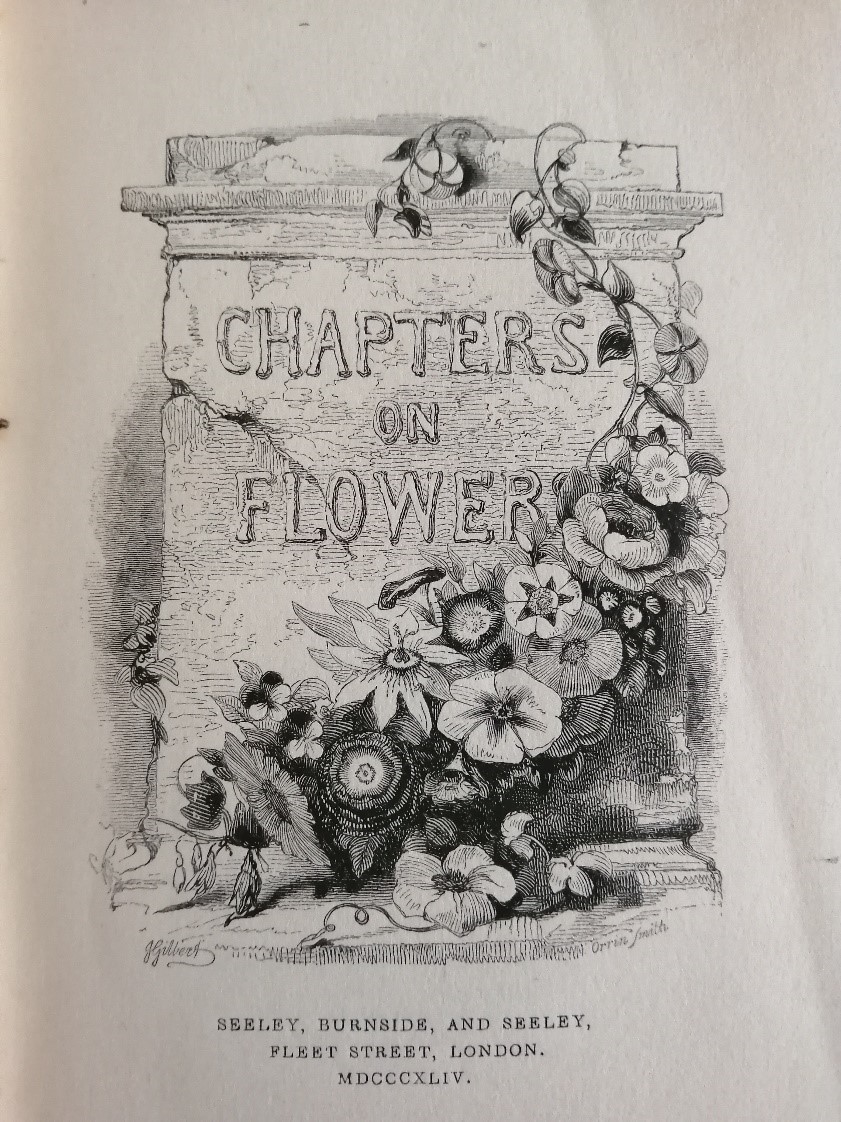

The language of flowers was a publishing craze allied to the keepsake, the gift book, or the gift annual. An import from France, Charlotte de Latour’s (Louise Cortambert’s) Le Langage des Fleurs (1819) was translated into English in 1834, and its adaptation and popularity spanned the length of the nineteenth century. Marketed specifically at women, the books were framed as sentimental items for display signifying social status and performative femininity, alongside their intended use as a means of managing love intrigues. Flowers were attributed human moods and emotions in the vocabularies or dictionaries of these publications, and they often included suggested bouquets to communicate through the silent sentiment of flowers. This may imply that the language of flowers had very little to do with death and mourning, however, the contents of the books frequently refer to the various life stages of the human and the flower, and thus, the final stage of death. As John Ingram notes,

The short and fragile nature of flowers has ever caused them to be regarded as types of the frail tenure of this existence.[i]

The links between death, memory and memorial are continually made in the language of flowers publications. They take the form of anecdotes and poetry concerning loss, of ruminations upon the use of graveyard flowers, as reminders of Biblical Design, and, the preservation of pressed and dried flowers kept to stir the memory.

We place them around the marble face of the dead in the narrow coffin, and they become symbols of our affections — pleasures remembered and hopes faded, wishes flown, and scenes cherished the more that they can never return.[ii]

The interconnections between the genres of literary annual and the language of flowers do, to an extent, account for the surprising allusions to death, memory and memorial in the language of flowers. Frederic Shoberl translated Charlotte de Latour’s language of flowers into English, and he was also the editor of a literary annual, the Forget Me Not, from 1822 to 1834. There is a reliance upon the sentimentality of grief and mourning across the textual and visual inclusions of both the literary annual and the language of flowers.

An instance of marginalia within a language of flowers book reveals that the publications might not only have been gifted as demonstrations of romantic or filial love, of friendship or gratitude, but also as tokens of memorial for the departed:

I read this dedication as:

For Elsie, In memory of her cousin Ethel Mary Cunnington who fell asleep, June 2nd 76 — G. Sulman

The deceased referred to could well be 18-year-old Ethel Mary Cunnington who died 2 June 1876 and is buried in Braintree Cemetery, Essex. Ethel’s monument inscription reads, ‘In the 18th year of her age. Fast in Thy paradise where no flower can wither’.

Floriography could help the bereaved to find a mode of expression that was derived from strong emotion yet was not overwhelmed by it. As a sentimental genre, the language of flowers perhaps contributed to a vocabulary for mourning that would negate much of the horror of death. This is in-keeping with what David McAllister has called an ‘aesthetic of death’. This aesthetic was culturally constructed, reliant upon sentimentality, and arranged to instil feelings of comfort rather than terror or horror.[iii]

An assembly of blooms in Robert Tyas’s The Language of Flowers; or, Floral Emblems of Thoughts, Feelings and Sentiments (1869) reflect a need to make use of floriography for consolation and sympathy. His bouquet contemplates the feelings of later life: ‘Periwinkle – Snowdrop – White Rose – Common Heath, are expressive of the consolation afforded in retirement by the remembrance of a well-spent life, “pleasant remembrances console us in the silence of solitude”’.[iv]

However, a variety of vegetal symbols associated with more sorrowful recollections can be found in the language of flowers. The idea of the forget-me-not as a symbol of remembrance is embodied in its name, as several editors of these anthologies point out. Miss Ildrewe, in The Language of Flowers (1865), notes:

A story is told in Germany, that two young lovers were walking on the banks of the Danube, when a cluster of flowers of celestial blue floated by on the stream. Struck by their beauty, the girl admires and regrets them. Her lover springs into the water, seizes the flowers, and has just time to throw them at her feet, crying, “Love, forget me not,” before he disappears in the swift current.[v]

From flos adonis to yew, and dead leaves to asphodel, floriography can reflect sadness and melancholy. The cypress represented death and mourning. In the first British language of flowers translation of 1834, cypresses impart ‘melancholy associations’, ‘resembling gloomy phantoms’ and presiding over ‘the abode of death’.[vi] They therefore had the potential to add a sombre note to any suggested bouquet — one floral combination in Robert Tyas’s The Sentiment of Flowers; or, Language of Flora (1836) weaves the forget-me-not, cypress and pimpernel together, meaning ‘Forget me not, for alas, we may never meet again’.[vii]

The marigold frequently equates to ‘grief’ or ‘inquietude’. As John Ingram mentions, ‘why so dazzling a bloom should have become the emblem of grief it is difficult to say, but in many lands it is regarded as such’.[viii] Literary tradition, the growing habits and life of the flower go some way towards informing the sentiment assigned to the marigold.[ix] Floral combinations could also modify its meaning: unite it with roses and it may signify the ‘bitter sweets and pleasant pains of love’, or bind it with cypress and it can symbolise ‘despair’.

Brent Elliott has suggested that the language of flowers was taken up in monumental masonry, and this has been noticed by others.[x] For example, Janine Marriott has analysed the floriography incorporated into gravestones at Arnos Vale cemetery in Bristol.[xi] The use of the language of flowers in the process of memorial was, then, significant. It mattered which flowers were included in rituals of mourning. A further example can be seen from 1874 with a ‘wills and bequests’ entry for John Wyatt in the Illustrated London News. Attendees at his funeral are instructed to wear ‘a white rose or camellia, or other white flower, in the buttonhole of his coat’.[xii] Although typically emblematic of love, the rose was, as Lizzie Deas suggests, ‘essentially a funeral flower’.[xiii] White rose could suggest ‘silence’, although in keeping with the notorious instability of the language of flowers, meanings did fluctuate. White rose also came to mean ‘I am worthy of you’, a dried white rose proclaimed ‘death preferable to loss of innocence’, a withered white rose conveyed ‘transient impressions’, and a white rosebud signified ‘girlhood’. The symbolism of the language of flowers altered and expanded as the century progressed. Sometimes, as with the white rose, this was dependent upon the stages of the flower’s own life cycle.

Gold, white porcelain | RCIN 65306

Royal Collection Trust

https://www.rct.uk/collection/65306/pair-of-brooches-from-the-orange-blossom-parure

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

One famous nineteenth-century figure associated with the language of flowers is Queen Victoria. This association frequently relates to bridal festivity and the symbolic value of the orange blossom to represent chastity — the Royal Collection Trust explicitly makes the link between the language of flowers and Queen Victoria in relation to the brooches displayed here (see above).

Queen Victoria on her death-bed, 24 Jan 1901

43.0 x 58.5 cm (whole object) | RCIN 450066

Royal Collection Trust

https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/6/collection/450066/queen-victoria-on-her-death-bed

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

However, Queen Victoria was again connected with the language of flowers upon her death, as seen in the portrait by Sir Hubert von Herkomer. White lilies were emblematic of ‘majesty’, ‘purity’ and ‘innocence’. As Lizzie Deas notes, ‘In keeping with its amatory character, the white lily is a funeral flower, and for maidenhood more particularly has long been laid aside.’[xiv] Considering also the silent, secretive aspect of communication that the language of flowers supposedly enabled, there is another interesting link with heath or heather which symbolised ‘solitude’. It has been suggested that the flowers strewn over Queen Victoria’s corpse were concealing items that she had requested to be buried with her, including heather from Balmoral and a photographic memento of John Brown. This is mentioned in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and details about the arrangements can be found in extracts from physician Sir James Reid’s diaries.[xv]

In summary, the language of flowers spoke to the themes of memory and memorial, both in terms of loss and grief, and celebration and consolation. These themes can be found not only within the language of flowers books but across the floriography of many nineteenth-century artworks and fictions. This, to me, indicates the diverse ways that the genre had infiltrated the cultural imagination: from romance to remembrance.

Jemma Stewart is a PhD student at Birkbeck, University of London. Her project examines floriography and the Victorian Gothic.

[i] John Ingram, Flora Symbolica; or, The Language and Sentiment of Flowers. Including floral Poetry, Original and Selected. (London: Frederick Warne & Co., 1869), p. 29 <https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.159895>.

[ii] Anon., ‘Introduction’, in The Poetry of Flowers; Containing Brief but Beautiful Illustrations of Flowers to which Sentiments have been Assigned: With Introductory Observations (London: James Williams, 1845). Available online https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/The_Poetry_of_Flowers_Containing_Brief_B/C4mRNb8kBHsC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=The+Poetry+of+flowers%3B+containing+brief+but+beautiful+illustrations+of+flowers+to+which+sentiments+have+been+assigned&pg=PA7&printsec=frontcover[accessed 27/01/2022].

[iii] David McAllister, Imagining the Dead in British Literature and Culture, 1790–1848 (London: Palgrave, 2018), pp. 154–55, p. 166 and p. 181.

[iv] Robert Tyas, The Language of Flowers; or, Floral Emblems of Thoughts, Feelings and Sentiments (London: George Routledge & Sons, 1869), p. xiv and p. 151 < https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.7581>.

[v] Miss Ildrewe, The Language of Flowers, with an introduction by Thomas Miller, Illustrated by Colored Plates, and Numerous Woodcuts, after Gustave Doré, Daubigny, Timms, and others (Boston: De Vries, Ibarra & Co., 1865), pp. 60–61 < https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.160068>.

[vi] Anon., The Language of Flowers (London: Saunders and Otley, 1834), pp. 134–36. Available online <https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=x6NgAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false> [accessed 28/01/2022].

[vii] Robert Tyas, The Sentiment of Flowers; or, Language of Flora, 2nd edn (London: R. Tyas, 1841), p. 110 <https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.169373>.

[viii] John Ingram, Flora Symbolica, p. 129.

[ix] Frederic Shoberl, The Language of Flowers; With Illustrative Poetry, 3rd edn (London: Saunders and Otley, 1835), pp. 147–49. Available online: <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/The_Language_of_Flowers_with_Illustrativ/-5NPAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=language+of+flowers+1834&printsec=frontcover> [accessed 22/01/2022].

[x] Brent Elliott, Occasional Papers from the RHS Lindley Library, Volume 10, The Language of Flowers (London: The Royal Horticultural Society, 2013), p. 48. Available online: <https://www.rhs.org.uk/about-the-rhs/pdfs/publications/lindley-library-occasional-papers/volume-ten.pdf> [accessed 17 November 2021].

[xi] Janine Marriott, ‘Secrets and symbols — the grave language of the Victorian cemetery’. Available online <https://arnosvale.org.uk/secrets-and-symbols-the-grave-language-of-the-victorian-cemetery/> [accessed 22/01/2022].

[xii] ‘Wills and Bequests’, Illustrated London News, 8 August 1874, p. 140.

[xiii] Lizzie Deas, Flower Favourites: Their Legends, Symbolism and Significance (London: George Allen, 1898), p. 13.

[xiv] Deas, Flower Favourites, p. 26.

[xv] Michaela Reid, Ask Sir James (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1987), p. 207, p. 216 and p. 215.