If you happened to wander around a Victorian garden cemetery in England, it’s not unlikely that you would stumble upon an Ancient Egyptian style (or ‘egyptianised’) grave. Whilst moss-covered obelisks and pyramids might seem a curious sight in predominantly Christian burial grounds to the modern viewer, it reflects a society that took delight in all things Ancient Egyptian.

This post will briefly explore what egyptianising mortuary structures found in landscaped Victorian cemeteries (or ‘garden cemeteries’) can tell us about the intersection of Egyptomania and Victorian death culture.

All we have of him is his pyramid; all we know of him is his name

For the average Victorian, travel to Egypt was rare, with a trip to the Pyramids being reserved for the wealthiest in society. However, there was still a large amount of public interest in Ancient Egypt, (known as ‘egyptomania) which influenced everything from architecture, literature, fashion and art, to the mortuary landscape.

Another way in which Victorians indulged their love of Ancient Egypt was through reading accounts written by people who were privileged enough to visit Egypt. One of the most popular examples was by writer and traveller Amelia B. Edwards. In her publication ‘A Thousand Miles up the Nile’, she recorded her trip to Egypt in great detail and spoke about the people and sights she encountered. This publication features a quote which is particularly fitting to the topic of Victorians and their egyptianising mortuary structures:

‘There is a wonderful fascination about this pyramid. One is never weary of looking at it – of repeating to one’s self that it is indeed the oldest building on the face of the whole earth. The king who erected it came to the throne, according to Manetho, about eighty years after the death of Mena, the founder of the Egyptian monarchy. All we have of him is his pyramid ; all we know of him is his name.’ [1]

The final resting places of ancient Egyptians remained as a permanent reminder—a name—of a life that was lived and filled with achievements, and perhaps for the Victorians, this idea of permanence, and of being able to display wealth and status for all time, was seductive.

However, it is important to note here that this obsession with Ancient Egypt was not without internal contradictions. The Victorians expected their corpses to be treated with respect and held the idea of a ‘final resting place’ in high regard. What they failed to do was extend this level of decency to the corpses of deceased Egyptians that were removed from their resting places, unwrapped for entertainment, and in some circumstances ground into paints or medicinal paste. [2]

Below the Surface

‘Garden cemeteries’ were privately owned, landscaped cemeteries that were built as a direct result of population changes and their effects on public health. These spaces were built away from the metropolis and were accessible to both mourners and the general public at a time before public parks were widely available.

The high regard for final resting places for the Victorians was more an ideal than the reality. In the Victorian era, above ground, the population increased rapidly. With the increase in the living came an increase in the dead. Things were particularly bad in cities like London, where graves in local Church yards were re-dug and corpses were dismembered or piled on top of one another close to the surface. What resulted was graveyards becoming (as Harold Mytum so poetically put it) a “foul smelling, slimy mass of putrefaction.”[3]

It was not only becoming increasingly impossible for mourners to grieve and for the dead to rest, but there was an added public health concern associated with protruding, sometimes exploding corpses of the metropolis. Health professionals of the time concluded that the condition of these corpses resulted in ‘Miasma’ (a toxic vapour), which was deemed to be the cause of public health problems such as cholera. In some cases, ‘Miasma’ was also thought to have been the cause of the untimely demise of those who interacted with corpses:

“A grave was opened in Aidgate churchyard, on Friday, and immediately, the pestilential exhumations destroyed the gravedigger.”[4]

There was mounting pressure on authorities to act and address the overcrowding of cemeteries. A series of ‘Burial Acts’ paved the way for the design and build of new ‘garden cemeteries’ which could be created with enough room to house the dead and the living who wished to pay their respects.

In 1833, The Standard newspaper reported on the proposed plans for the build of Highgate Cemetery. The brief article summarised that the abandoned state of the current churchyards impacted loved ones’ ability to visit their deceased relatives to leave flowers and goes on to state that “such a cemetery [Highgate] as the one proposed would rouse feelings of virtue and bravery in the hearts of mankind”. [5]

Valley of the Victorians: The Magnificent Seven

The Magnificent Seven cemeteries are made up of Kensal Green, West Norwood, Highgate, Abney Park, Nunhead (originally All Saints), Brompton and Tower Hamlets. In England, these privately owned burial grounds were the first example of garden cemeteries and often featured elaborate monuments, grave markers and mausoleums.

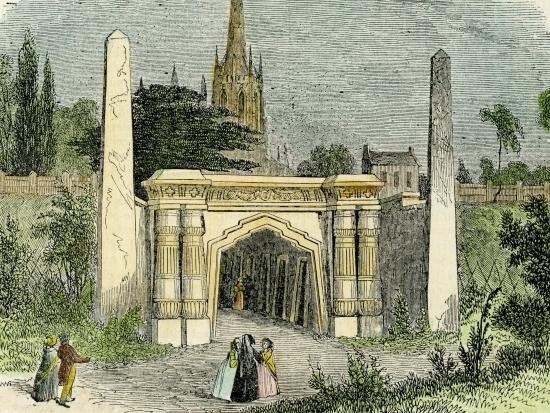

Here, Highgate is the obvious choice when we think about egyptianising mortuary structures in England due to the design of the entrance to Egyptian Avenue in the Western part of the cemetery. The imposing Egyptian Avenue spoke to a public with an appetite for Ancient Egypt. The gateway and two large obelisks were designed by architect Stephen Geary and were reminiscent of an Ancient Egyptian temple. When visitors walked through the gates, they would be able to view 12 family vaults. In 1865, an accompanying guide to Highgate Cemetery was published. Within its pages we find some insight as to how the Egyptian Avenue would be experienced by Victorian visitors and potential customers:

“As we enter the massive portals and hear the echo of our footsteps intruding on the awful silence of this cold, stony death-palace, we might almost fancy ourselves treading through the mysterious corridors of an Egyptian Temple.” [6]

As impressive as the Egyptian Avenue is, arguably, the façade of Abney Park might be the most accurate copy of ancient Egyptian structures in the context of a mortuary landscape in England. Designed by William Hoskings, with assistance from Joseph Bonomi the Younger, both the capitals to the columns of the lodge and the hieroglyphs present have been produced with care and exceptional detail. Most notably, the hieroglyphs are not mere copies of various symbols, but make a meaningful sentence:

“The gates of the abode of the mortal part of man” [7]

Graves of Note

Victorians who purchased egyptianised graves tended to be wealthy, and in some cases, they had direct links with Egypt.

For example, the aforementioned Amelia B Edwards, is buried beneath a stone representation of an Ankh, the Egyptian hieroglyphic symbol meaning ‘life’, and can be found in St Mary’s Church in Henbury [8]. Her career, travels, and creation of the Egypt Exploration Society [9] provide us with an easy answer as to why an egyptianised grave was chosen in this instance.

Similarly, the grave of Architect and Egyptologist Joseph Bonomi the Younger, which can be found in Brompton Cemetery [10] is another example where it’s easier to find a reason for the choice of an egyptianised grave. Joseph is buried beneath a rather plain looking headstone, but if you look to the bottom, there’s an egyptianised engraving which appears to show the God Anubis.

Finding out why Victorians who had no obvious associations or interest in Egypt chose these types of burials is sometimes made more difficult by the local lore that surrounds them. Even though local tales (such as the ones below) about pyramid graves and time machines should be taken with a pinch of salt, they are good examples of gothic stories that continue to be inspired by egyptomania.

Hannah Courtoy 1784-1849 (Brompton Cemetery)

The first rumour about Hannah Courtoy’s resting place is that her tomb was designed by Bonomi the Younger. One of the more interesting tales is that the mortuary structure is actually a time machine, which apparently stems from the idea that Bonomi learned the secret to time travel in Egypt. When he returned, he is said to have worked with an inventor named Samuel Alfred Warner to build the ‘machine’, for which the key has been missing for over a century.

Hannah’s life however, is no less interesting than the time machine. She had three children out of wedlock, and mysteriously inherited a large fortune from a man named John Courtoy. Although they never married, she took his name, and later died in one of the most expensive areas of London. [11]

William Mackenzie 1794-1851 (Rodney Street, Liverpool)

If you happen to find yourself on a ghost tour in Liverpool, or propping up a bar near Rodney Street, then you might stumble upon (one of a number of variations of) the story of William Mackenzie’s 15ft pyramid. The tale begins with him gambling on Rodney street one dark and foggy night in Liverpool. The cards weren’t in his favour, and so a man who revealed himself as the Devil, offered him a way out. He said William could win back his fortune and property, but if he loses, when he was 6 feet underground, the devil would return to claim his soul.

The story goes that William lost, and upon his death, erected the huge pyramid in which he is seated at a table, above ground, with a winning hand of cards. Variations of the tale are rife, with some stating that he is sat upright with a roast dinner. The truth, although less exciting, is that he was a perfectly ordinary wealthy Victorian, and the pyramid was actually erected years after his death, by his brother. [12]

‘Mad Jack’ Fuller 1757-1834 (St Thomas a Beckett Church – Brightling)

John Fuller was a British politician, known ‘drunk’, and supporter of the evils of slavery who was known as ‘Mad Jack’ Fuller.

The theme of the roast dinner continues with Fuller’s 25ft pyramid grave, which was erected prior to his death. Locally he is rumoured to be sat upright at a table, wearing a top hat, with a roast dinner. References to the devil can once more be found in the tale of Mad Jack tale, where some variations of the local tale state that shards of glass have been placed around the tomb to prevent the devil from taking his soul. [13]

Afterlife

This post has only scratched the surface into the research I have been undertaking into the complex reasons why people chose to be buried in egyptianising graves in Victorian England. Each person buried has a unique story and different reasons for wanting their final resting place to look the way it did, whether it be a pyramid structure or a simple obelisk design.

It’s easy, as a modern person interacting with these mortuary structures to make assumptions about the person buried underground and to get caught up in the (often hazy) details of their monument choices whether that be a personal interest in Ancient Egypt, a showcase of wealth, a subtle nod to religion, or a symptom of egyptomania.

Wealth undoubtedly played a part in the amount of choice people had in choosing their egyptianised resting place. As interesting and beautiful as these structures are, it’s evident that there was a price to being remembered, highlighting the unfairness of burial practice (and society) in Victorian England.

As many of our garden cemeteries remain open to explorers, one thing we can say for certain is that if the purpose of some of these interesting structures was simply for people a century down the line to be drawn to their grave, read the inscription and know that they were once here, then the goal has been achieved.

Michelle Keeley-Adamson is a graduate of Egyptology (MA) from Liverpool UK. When she isn’t working her day-job, is undertaking independent research on all things Joseph Bonomi the Younger and Egyptomania in Victorian England.

Sources:

[1] Amelia B. Edwards – A Thousand Miles up the Nile (see pp.47-68) An online version is available here: A Thousand Miles Up The Nile. (upenn.edu)

[3] Mytum, Harold. “Public Health and Private Sentiment: The Development of Cemetery Architecture and Funerary Monuments from the Eighteenth Century Onwards.” World Archaeology, vol. 21, no. 2, Taylor & Francis, Ltd., 1989, pp. 283–97

[4] “CHURCH-YARDS IN LONDON.” Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle [London, England] 9 Sept. 1838: n.p. 19th Century UK Periodicals. Web. 6 Mar. 2019.

[5] The Standard (London, England), Thursday, July 25, 1833; Issue 1935. British Library Newspapers, Part II:1800-1900.

[6] Guide to Highgate Cemetery by William Justyne 1865 https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015043572810&view=1up&seq=38

[7] Elliott, Chris. “Compositions in Egyptian Hieroglyphs in Nineteenth Century England.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 99, Egypt Exploration Society, 2013, pp. 171–89, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24644932.

[8] Grave of Amelia Edwards, Non Civil Parish – 1439170 | Historic England

[9] Amelia Edwards: Writer. Adventurer. Explorer. | Egypt Exploration Society (ees.ac.uk)

[10] Joseph Bonomi (1796-1878) – Find a Grave Memorial

[11] Blog on Mackenzie’s Tomb by Tetisheri: https://tetisheri.co.uk/the-tomb-of-the-gambler/

[12] The Tomb Of Hannah Courtoy – London, England – Atlas Obscura

[13] Mad Jack Fuller Folly Trail – Brightling Park

[14] Clipping from: Hackney and Kingsland Gazette – Friday 18 December 1896 – – British Newspaper Archive

Further Reading/Watching:

Fay, E. 2001. “The Egyptian Court and Victorian Appropriations of Ancient History” Romanticism and interdisciplinarity: “centers and peripheries”, 32: 24-29

Whitehouse, H. 2003. Egypt in the Snow. in, Price, C. & Humbert, J.M.(eds.) Imhotep Today: Egyptianising Architecture Australia: Cavendish Publishing

Highgate Cemetery Through Victorian Eyes (ON DEMAND RECORDING) Tickets | Eventbrite

The Magnificent Seven – British Guild of Tourist Guides (britainsbestguides.org)

Fuller’s Follies – Visit 1066 Country Joseph Bonomi the Younger – Brompton Cemetery – The Royal Parks