WARNING: This post contains images of and explicit discussion regarding the human corpse.

The corpse in contemporary art is a transgression of boundaries. It is a taboo not often seen in a gallery setting, let alone in our everyday lives. When we engage with artworks that involve the corpse – as subject matter or medium – we endure anything from fear to repulsion, fascination to curiosity. Often all these feelings at once. As depicted in the artworks of American photographer Sally Mann (b. 1951) and Mexican multi-media and conceptual artist Teresa Margolles (b. 1963), the corpse challenges the taboo that it should remain out of sight and untouched. In art, the corpse pervades the psyche and physical domain of the living. While these artworks will not offer hidden truths about death or an afterlife, they prompt us to consider our reactions to the dead body and, more generally, our inevitable deaths.

Gelatin silver print with varnish, 76.2 x 101.6 cm. Gagosian, New York.

Image via artist website.

In the early 2000s, Sally Mann produced a photographic series focused on the Forensic Anthropology Centre in Tennessee. Commonly known as The Body Farm, the three-acre plot is home to donated corpses, monitored by students who study decomposition in aid of forensic science. Mann produced the series Body Farm as part of a larger body of work, which she describes as an investigation into how “the land subsumes the dead,” transfiguring them into “the rich body of earth, the dark matter of creation.” [1]

Untitled (Maggots) [fig.1] is a black and white photograph depicting the head and shoulders of a decomposing corpse, face-down in a thicket. Specifically, it’s a silver gelatin print made using a nineteenth-century photographic technique called wet-plate collodion. Mann began using the method in the 1990s, and it gives her photographs an antique, almost sculptural quality. The technique was popularised in the 1850s by documentary photographers, such as Mathew Brady, who captured the horrors of the American Civil War [fig 2].

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Compared to other methods of the time, wet-plate collodion was fast, produced impressive tonal variety, and allowed artists to reproduce their prints. However, it was also messy, highly flammable, and involves a lot of heavy equipment, making it an arduous practice. It demands long exposure times, the effect of which is visible in the diaphanous triangular veil that extends from the shoulder, across the forehead and into the earth, concealing decay in Untitled (Maggots) [fig.1].

The developing process is erratic: it produces tonal abnormalities, streaks, and often portions of disintegration in the final proof. Mann embraces the medium’s fragility and retains imperfections in her final prints. In the same image, note the shark-fin shaped cut that protrudes from the center of the bottom edge, and in Untitled (Curtain) [fig. 3], disintegration takes over almost a quarter of the picture. These imperfections reveal the photograph’s materiality, and as it appears to deteriorate, it articulates the corpse’s decomposition. At 75 x 100cm, the bodies in Mann’s photographs are almost life-size, and therefore decay is interpreted through the living body of the viewer.

Gelatin silver print with varnish, 76.2 x 101.6 cm. Gagosian, New York.

Image via artist website.

To the modern eye, this style of photography – especially the monochromatic palette – holds associations with truthfulness and documentary, and Mann applies this vernacular to the image of the corpse. This next image is a colour print of Untitled (Maggots) [fig. 1], from Mann’s autobiography, Hold Still.

Reproduction from Mann, Sally. Hold Still: a memoir with photographs. First edition. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2015; 427.

The hazy veil in the colour print reveals a socket teeming with maggots, dripping with brown goo. The body is bloated, its skin peeling from sunburn and exposure, and the hair is slick with dew, indicating the dampness of the earth where it lays. It’s a valuable point of comparison for the silver gelatin print because it reveals both the reality of the exhibited image and the ways in which Mann has aestheticised it. The black and white version is not only beautiful but conceals the subject matter to an extent. Momentarily disarmed, it takes a moment to realise what you’re looking at.

Mann’s photographs are part-documentarian, part-aestheticised, but a wholly poignant reflection on the materiality of our corporeal form, which is ultimately as fragile and brittle as the medium she works in. In terms of proximity, Mann’s photographs provide a safe distance. Although her photographs facilitate an encounter between viewer and corpse, as in, one can witness another time and place, they cannot physically participate.

Conversely, Teresa Margolles employs techniques that coerce the spectator to engage and react, often physically implicating them in the artwork. Much of Margolles’ early work draws on her experiences as a forensic pathologist in Culiacán, Mexico and responds to narco-violence along the Mexican-US border during the 1990s. Lengua [fig. 5]is a preserved human tongue pierced by a metal rod and bar accessory. It’s displayed on a metal plinth, resembling a readymade.

Figure 5: Teresa Margolles, Lengua [Tongue], 2000. Object, human tongue, metal bar and road accessory, dimensions unknown. Courtesy of Teresa Margolles and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich.

Reproduction from Banwell, Julia. Teresa Margolles and the Aesthetics of Death. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2015; 93.

Readymade is a term borrowed from the oeuvre of Marcel Duchamp, who presented mass-produced everyday objects as art. You might recognise his work, Fountain [fig. 6], an upturned urinal, which he signed and placed in a gallery in 1917. Lengua creates a cognitive challenge to the viewer by invoking the art historical legacy of the readymade. As an object, the tongue has been displaced from its natural environment and shown devoid of the human body. It begs the question of how it came to be in a gallery.

Figure 6: Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917. Installation photograph by Alfred Stieglitz at the 291 following the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibit, with entry tag visible.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Margolles states that Lengua belonged to a young man, beaten to death in a street fight. When his body reached the morgue as an unidentified victim, she located his family and attained permission to use his body in her artwork. Of the encounter, she said, her job was to convince the boy’s mother that “her son’s body would speak of the thousands of anonymous deaths that people don’t take into account.” [2] This artwork visualises the effects of narcoviolence in the streets of 90s Mexico, the unidentified, unclaimed bodies in its morgues and the institutional culture of laxity that legally permits the use of the corpse in this way.

Presented in this manner, Lengua immediately draws attention to the absence of the whole. As a medium, it is inherently abject in that it reminds us of our living bodies. Margolles’ use of human materials can by understood as symbolic of the fragmentation of the body after death, be it through decay, autopsy or disassembly for scientific study. As Julia Kristeva says the corpse evokes the strongest sensations of abjection in that it shows us decomposition – “what we permanently thrust aside in order to live.” [3] Specific to the tongue, Lengua functions as a non-secular relic, removed from the body and displayed for meditation, speaking for the victims of violent deaths who have been abruptly silenced.

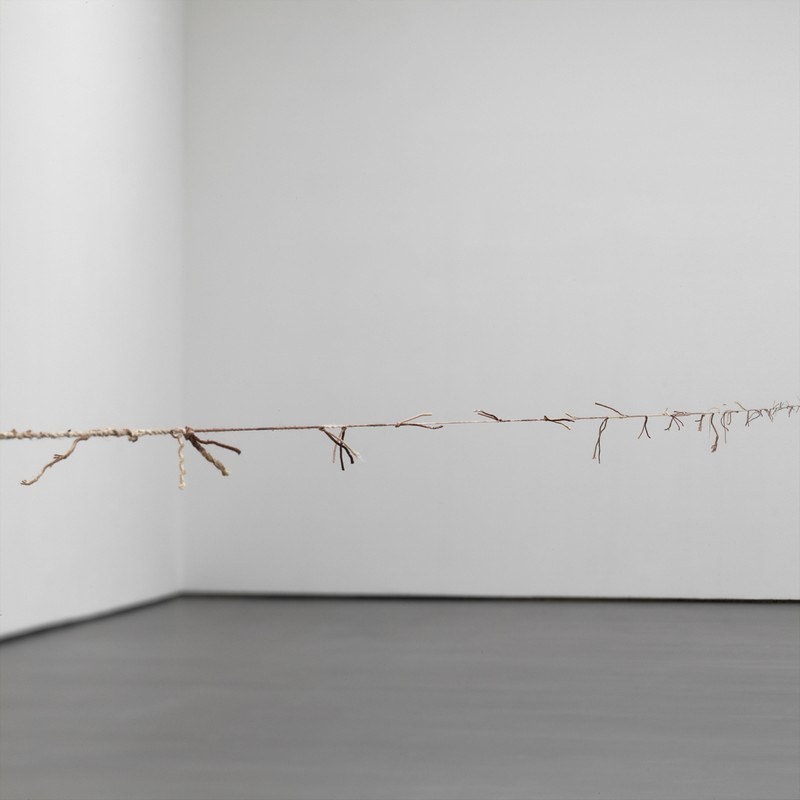

127 Cuerpos [fig.7] is an installation comprising 127 pieces of thread knotted together across the gallery space. Suspended at waist height, this aggregate of thread cuts off a third of the room. As viewers get close, it becomes clear that the thread is unevenly stained. Margolles utilises a minimalist mode forcing the viewer to inspect the thread because there is little else to take visual refuge in. Part way down the gallery is a wall-text. It reveals that the thread has been used during autopsies. In a metonymic reading, each thread is a corpse, and the residue thereof acts as a shorthand for the absent whole.

Courtesy of Teresa Margolles and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich. Photo: Achim Kukulies.

Reproduction from Downey, Anthony. “127 Cuerpos: Teresa Margolles and the Aesthetics of Commemoration.” In Understanding Art Objects: Thinking through the Eye, edited by Tony Godfrey, 104-113. Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2009.

As art historian Anthony Downey argues that these stains are hardly representational or abstractions but instead the “re-presentation of death itself” manifest in a perceptible object. [4] He likens them to the Sudarium of St Veronica, a Catholic relic revered for having wiped the face of Christ as he carried the cross [fig 8]. The threads in 127 Cuerpos present an impression created by the body’s torsion, which reifies the absence of the physical corpse. Viewers are implored to consider the lives of the deceased, as well as the afterlife of their physical form.

Samuel H. Kress Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Image via NGA

Margolles employs a coercive method of immersion in her installation works, which inhibits the audience’s ability to turn away from death. Vaporización [fig. 9] is a powerful example of this: the audience enters a dimly lit room submerged in humidified air. Vapour enters the body, is absorbed by the skin, and inhaled into the lungs. It is inescapable, and without knowing the origin of the water, this could be a profoundly beautiful experience. The water, however, has been used to wash corpses in the morgue.

Figure 9: Teresa Margolles, Vaporización [Vaporization], 2001. Installation with 1- 2 smoking machines, dimensions variable) edn of 4 + 1 AP. Installation image of PS1 exhibition Mexico City: An Exhibition about the Exchange Rates of Bodies and Values. Image via MoMA PS1 Archives.

The immersive power of this work is in its embodied qualities. The corpse becomes tactile in the heat of humidification; its weight settles on the skin and soaks through clothing. The room is hazy, augmenting the way visitors move through the space – often with trepidation of the unknown. Their own bodies are nothing more than a misty outline. The corpse remains out of sight, yet it is an active presence. The viewer touches the corpse, but the corpse also touches back as we inhale, enacting a kind of haunting. The most fundamental biological process — breathing — defines a living body, but in Vaporización, it dissolves the distinction between subject and object, viewer and artwork, living and the dead.

Death is a boundary, and the corpse complicates this threshold, positing an experience that extends beyond our finite end. When bodies spill out of their boundaries, they become unsettlingly other. Engaging with art that depicts the corpse as a subject or medium allows us to navigate the abject and interrogate a myriad of sensations and psychological reactions. Within the context of the gallery, an encounter with a corpse can be confronting, but ultimately, it has the power to demystify what is usually hidden from view.

––

Maya Love (she/her) is a writer and researcher based in Aotearoa, New Zealand. She’s working on her PhD in Art History at Waipapa Taumata Rau University of Auckland exploring the significance of the corpse in contemporary art. She’s also the grave keeper at d_composition, a blog breaking down the corpse in art + all manner of the macabre.

––

[1] Mann, Sally. What Remains. Boston, MA: Bulfinch Press, 2003. 6.

[2] Maria Campiglia translated by Vásquez, Natalia A. “(Re)presenting the Missing: The Artworks of Teresa Margolles and Oscar Muñoz.” Masters Thesis, Leiden University, 2015. https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/36448. 10.

[3] Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: an essay on abjection. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982. 3.

[4] Downey, Anthony. “127 Cuerpos: Teresa Margolles and the Aesthetics of Commemoration.” In Understanding Art Objects: Thinking through the Eye, edited by Tony Godfrey, 104-113. Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2009. 107, 110.