Let us take a moment to glance at the brighter side of death and peer ‘beyond the veil’ at some amusing narratives emanating from the Victorian séance room. In considering light-hearted episodes from Punch, a scathing dramatic monologue from Robert Browning, and a mischievous scene from a popular Spiritualism memoir, we can glimpse the humorous side of Spiritualism, an immensely popular nineteenth-century movement concerned with spirit-world contact which heralded death as a beginning, not an end.

I begin with a caveat that, while researching for this blog (and indeed when conducting the majority of my research into nineteenth-century Spiritualism) my humour dial is very much set to Victorian, so please be generous with your expectations for the relative ‘hilarity’ that these nineteenth-century jests generate for modern-day readers.

Spiritualism began in 1848 in the town of Hydesville (New York) when two young sisters, Kate and Maggie Fox, purportedly made contact with spirits lingering in their home through a series of knocks, or rappings. The Fox Sisters were celebrated as mediums due to their powerful connections with the spirit world and showcased their inexplicable psychical abilities through public séances that hundreds paid to attend.

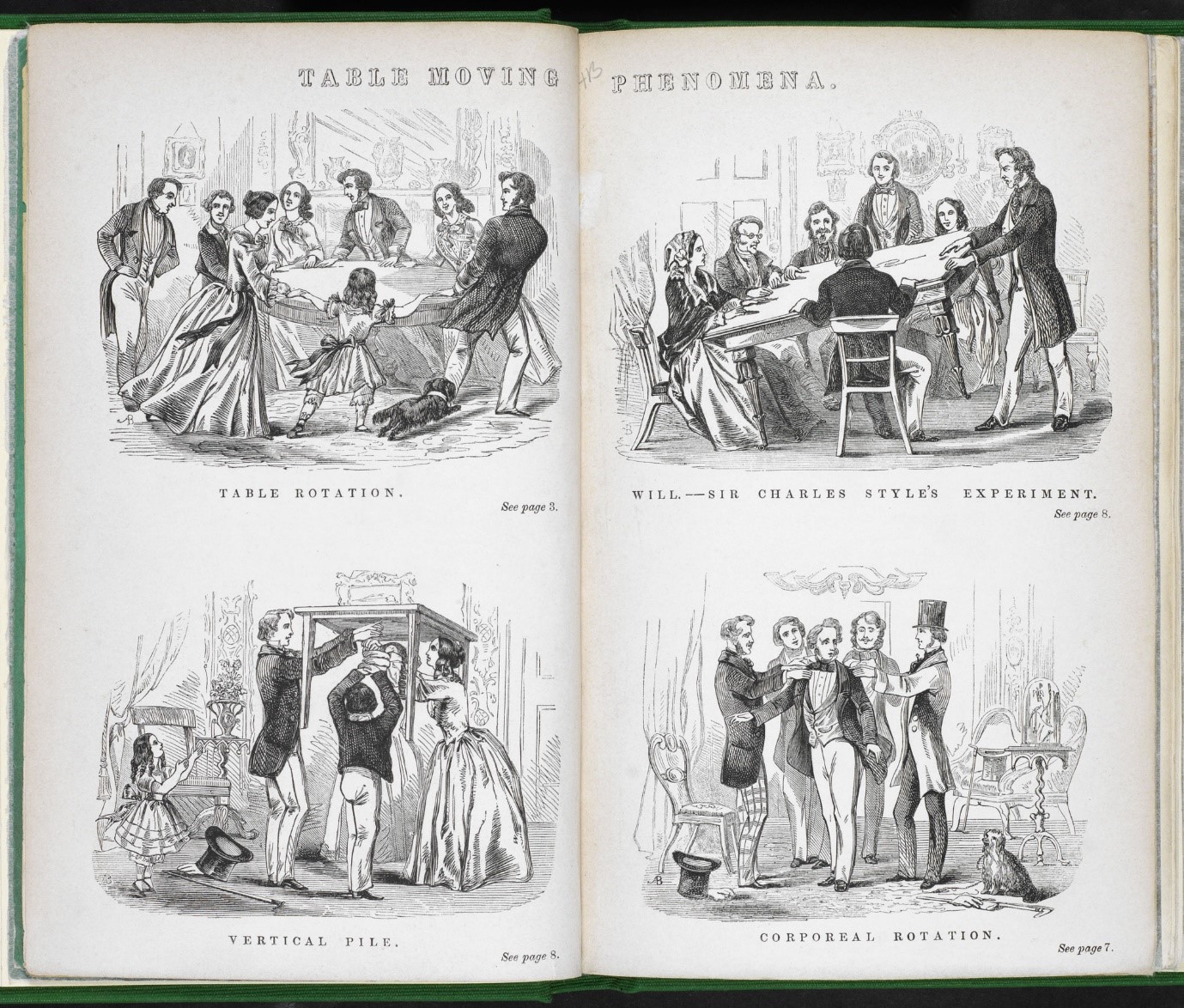

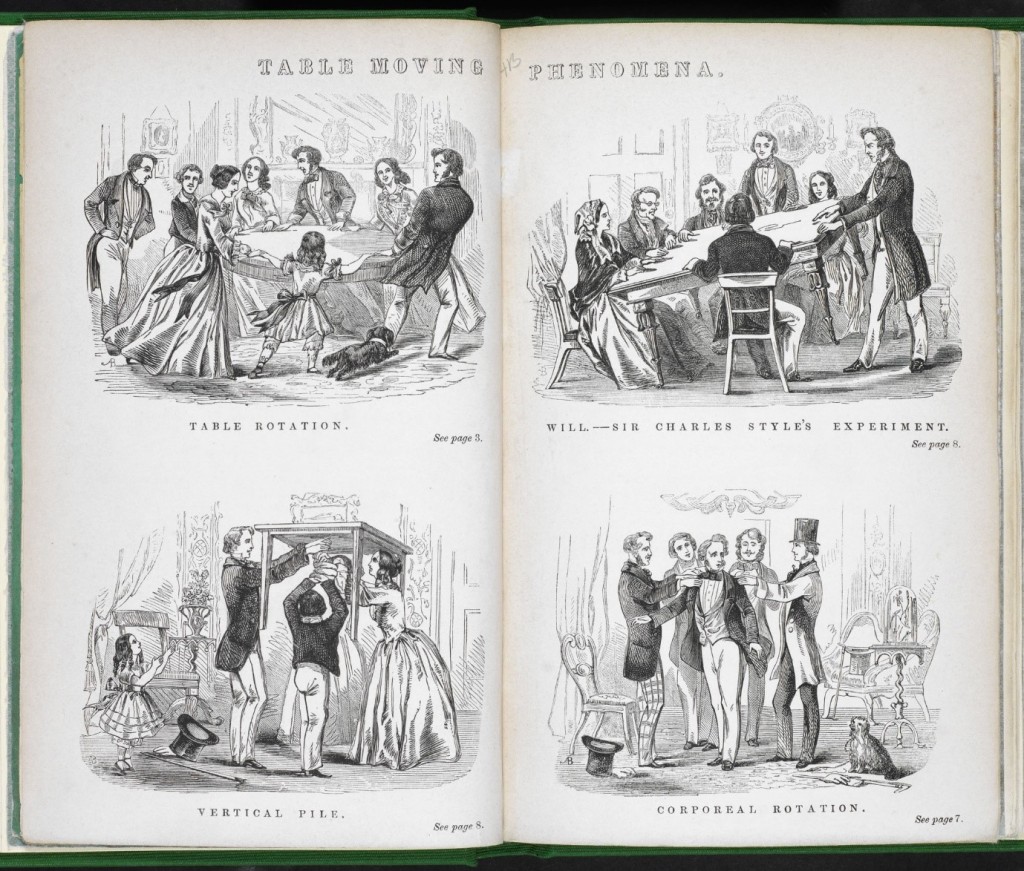

It is from this exhilarating climate of paranormal activity that the séance (a word literally meaning session, sitting, or meeting) thrived. Séances usually involved a medium receiving messages from the ghosts of the departed in a variety of ways, including table-turning, ‘channelling’ the spirit’s identity when in a trance, a spirit (or Ouija) board, automatic writing, musical contact, or the creation of spirit-art. The sensational spectacle of the séance meant that it could be easily commercialised as its manifestations morphed from public performance to domestic pastime. Spiritualism became extremely popular in Britain after its traversal of the Atlantic in the early 1850s; British author, Margaret Oliphant, observed it as an ‘invasion’ into mid-Victorian society and culture, while Punch affirmed it was ‘practised daily by tens of thousands’.[1]

1850s editions of the illustrated satirical periodical, Punch, or the London Charivari (1841 – 1992), demonstrate how Spiritualist table-turning (also referred to as table-tipping, table-moving, and table-talking) had an insatiable appeal as a ‘principal amusement’.[2]

In 1853, Punch mocked the exaggerated execution of public table-turning displays by parodying an advert for an oversaturated market of Spiritualist Christmas performances from a ‘Theatre Royal Anywhere’, in which they centralise three ‘Reverend Mountebanks’ who, as they humorously remark, ‘go the whole hog, or rather the whole ma-hog-any’. Punch jokingly imagines the levitating tables as pageant horses in training and dramatises a ludicrous performance in which the ‘astounding table will dash through an open window, spin round for a quarter of an hour, and conclude its wonderful performance by leaping out of the circle, with the Reverend Sampson Spooney hanging on to its castors’. The feature proceeds to mock ‘six dining-tables in full gallop, all of which will take an astounding leap over each other’s backs; and conclude by throwing a succession of somersets [sic] over a sideboard’.[3]

Hyperbole is a vital weapon in Punch’s arsenal and its use here dramatically vivifies the amusing visual phenomena associated with supposed paranormal contact. In addition, by imbuing the tables with animal agency ̶ which suggest taming supernatural spirits as if they were horses – Punch reiterates the domestication of the Spiritualism movement: one which sought to tame the inexplicable by bringing the pageantry of public séance performances directly from the theatre, and into the home.

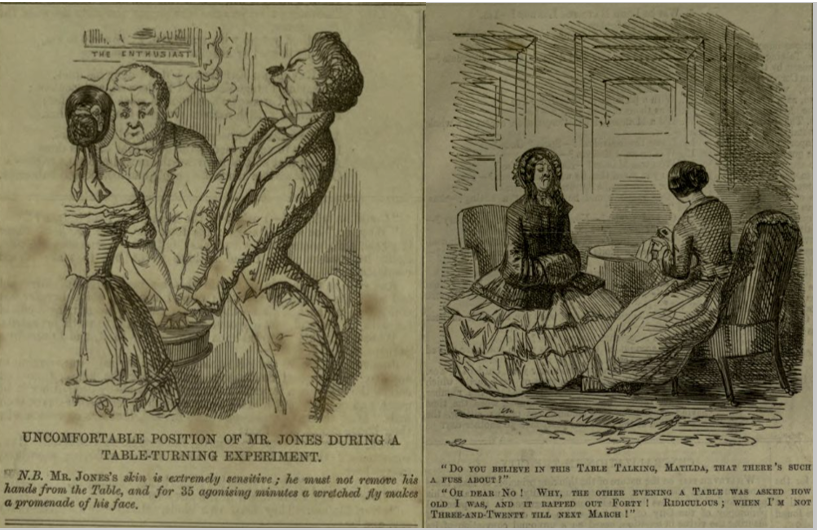

Punch, with its characteristically unapologetic style, parodied séance activities to bring attention to all things uncomfortable. Whether that meant the physical discomfort of lengthy sittings with spirits, or confronting unpleasant truths which revealed the not-so-secret world of the living. The caption under the above left cartoon stresses ‘the uncomfortable position of Mr. Jones during a table-turning experiment’, comically noting that ‘Mr. Jones’s skin is extremely sensitive; he must not remove his hands from the table, and for 35 agonising minutes a wretched fly makes a promenade of his face’.

In the second cartoon, a young woman asks an elder lady if she believes ‘in this table talking […] that there’s such a fuss about’. The discernibly older woman retorts: ‘Oh dear no! Why, the other evening a table was asked how old I was, and it rapped out forty! Ridiculous; when I’m not three-and-twenty till next March’. Here, the revelations of the spirit-world are far from welcome as they disclose awkward information about the elder woman’s true age. The wealthier dress and pompous expressions of the characters suggest Punch’s targeted jabs at upper-class or aristocratic Spiritualism enthusiasts. They are observed practising Spiritualism as a form of entertainment, yet the humour exposes the fickle nature of these wealthy individuals who reject their favoured pastime when it poses unsavoury threats to Victorian propriety.

Punch also turns the tables on the furniture itself, with jibes which target the ‘suspected Satanic agency in some portions of our furniture, particularly in a quantity of cheap stuff which we purchased at a furniture mart, and which is scarcely worth the rap we have bestowed on it’.[4] They make cringe-worthy puns about ‘a round table which is subject to fits of groaning and creaking, with an occasional tendency to the splitting of its sides, as if in very mockery of merriment’.[5] And they take jabs at sneaky servants: ‘We do not see why the presence of the evil one should be confined to the work of the cabinet-maker or the carpenter, […] Our own stock of crockery is undoubtedly exposed to such contingencies, for we now and then find an amount of breakage which, if our servants are to be believed, has not been done by any earthly agency’.[6]

Aviva Briefel reinforces the mischievous characterisations of spirit-possessed furniture in her 2017 article, ‘“Freaks of Furniture”: The Useless Energy of Haunted Things’. She observes how ‘accounts of spirit mishaps, whether delivered with skepticism or belief—or, as was often the case, with a little of both—depict the chaos that ensues with the animation of household objects. Haunted things misbehave. They throw interiors into disarray, pull juvenile pranks, irreverently mimic human behavior’.[7]

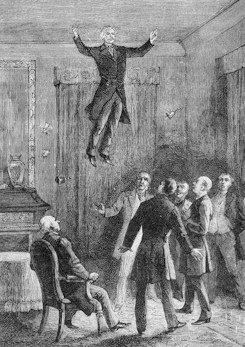

One of the most notorious subjects of Spiritualism-inflected ridicule was the infamous Scottish physical medium, Daniel Dunglas Home, who held several well-publicised séances which were investigated in the early 1870s by William Crookes. Celebrated escape artist Harry Houdini later reflected that Home was ‘one of the most conspicuous and lauded [mediums] of his type and generation’ and remarked that, evidently, ‘the spirits were good to him’.[8]

In 1874, after years of experiments, Crookes claimed that Home was the ‘the most remarkable’ of mediums imbued with a genuine ‘Psychic Force’. Concerning Home’s apparent abilities to levitate objects, make bodies weightless, and play musical instruments (specifically the accordion) without human interference, Crookes concluded that he was decidedly ‘convinced of their objective reality’.[9]

Robert Browning, on the other hand, was a figure who vehemently refuted assessments of Home like that of Crookes’, following his own first-hand experience witnessing Home’s purported supernatural abilities. In response to attending what Browning deemed to be a fraudulent séance led by Home in 1855, Browning wrote a dramatis personae entitled, ‘Mr Sludge: ‘the Medium’’ (1864), which, as Richard Kelly stresses ‘is clearly an embroidery of the poet’s keen first impressions of Daniel Home’.[10] It is a bold, scathing, and often amusing attack on the séance room presented as a lengthy dramatic monologue. Its opening shows ‘Mr Sludge’ pleading not to be exposed as a fraud after being caught cheating:

‘NOW, don’t, sir! Don’t expose me!

Just this once! This was the first and only time, I’ll swear,—

Look at me,—see, I kneel,—the only time,

I swear, I ever cheated,—yes, by the soul

Of Her who hears—(your sainted mother, sir!)

All, except this last accident, was truth—

This little kind of slip!—and even this,

It was your own wine, sir, the good champagne,

(I took it for Catawba, you’re so kind)

Which put the folly in my head!’

Turning to his host, Mr Sludge blames inebriation ̶ ‘your own wine, sir, the good champagne’ ̶ for galvanising his fraudulent ‘folly’ in a desperate plea to preserve his mediumistic reputation. Isobel Armstrong reinforces that ‘Mr Sludge’ ‘was a provocative attack on spiritualism’ which, at the time, ‘aroused some controversy’, despite its amusing overtones.[11]

Florence Marryat was a prolific Victorian author of sensation and Gothic fiction, as well as being renowned as a key populariser of the late-Victorian Spiritualism movement. Marryat, however, also became a polarising public figure and the subject of journalistic mockery at the fin de siècle. One scathing 1894 article in the Saturday Review questioned Marryat’s mental capacities due to her belief in the spirit world at a time when many celebrated mediums and spirit photographers had already been discredited and exposed as frauds. They express their concern that ‘Miss Marryat, we fear, has not nearly enough sense to mind […] tables have rapped and wobbled, banjos have thrummed […] people who indulge in these amusements have […] learnt positively nothing since Mr. Browning’s “Sludge” put them in their places once and for all’.[12]

Authors George and Weedon Grossmith took their derision to a more personal level, satirising Marryat’s unconventional two marriages and vague relationship status by parodying her in their hilarious precursor to Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996), ‘The Diary of a Nobody’ (1892): ‘I found Carrie buried in a book on Spiritualism, called There is no Birth, by Florence Singleyet’. Despite their mockery, the Grossmiths dedicate a whole chapter of their book to experiments with Spiritualism which they stress come as a direct result of Marryat’s memoir There is No Death (1891), a book they declare ‘[a]ll the world is going mad over’.[13]

Published in 1891, There is No Death detailed Marryat’s first-hand experiences of séances and sittings held with the period’s most renowned mediums. Before attending her first séance, Marryat highlighted the movement’s polarising nature: ‘I had heard it mentioned by some people as a dreadfully wicked thing, diabolical to the last degree, by others as a most amusing pastime for evening parties’. Laying out her ultimate goal for the narrative, Marryat revealed her intention that, by sharing the precise details of the séance phenomena she had witnessed, she hoped to prove the ‘science of Spiritualism’.[14]

Though there are many humorous gems to be discovered in Marryat’s memoir, I close with one in which Marryat reveals the impish timbre of the spirit world (and its puckish spectral inhabitants). She recounts the ‘control spirit’ of a famous medium, Bessie Fitzgerald, named ‘Dewdrop’ who ‘was very fond of going to the play, and her remarks were so funny and so naïve as to keep one constantly amused. Presently, between the acts, she said to me, “Do you see that man in the front row of the stalls with a bald head, sitting next to the old lady with a fat neck?” I replied I did. “Now you watch,” said “Dewdrop;” “I’m going down there to have some fun. First I’ll tickle the old man’s head, and then I’ll scratch the old woman’s neck”’.[15]

Not only does Marryat’s memoir seek to defend the serious ‘science of Spiritualism’ and the gravity of séance communications, Marryat, like Punch and Browning before her, celebrates the opportunity to scoff at spirits, ultimately capturing the humour and mischief which accompanied table-talking with the dead.

Biographical note:

Emily Vincent (she/her) is a final-year PhD researcher in English Literature at the University of Birmingham. Emily’s recently submitted thesis explores how women navigate child loss in fin-de-siècle ghost stories by examining Spiritualism and maternity in the supernatural works of Florence Marryat, Margaret Oliphant, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Emily has worked as a Teaching Associate for Birmingham’s English department and Academic Writing Advisory Service, and Research Assistant for Birmingham’s Nineteenth-Century Centre. Emily also co-founded Gothica, Birmingham’s interdisciplinary reading group on the Gothic. Emily is currently Co-Deputy Associate Director of Research for the Centre for Nineteenth-Century Studies International, based at the University of Durham.

[1] M. O. W. O., ‘Mrs. Craik’, Macmillan’s Magazine, (1887), 81-85 (P. 82); ‘Table Turning and True Piety’, Punch, vol. 25 (1853), p. 243.

[2] ‘Tea-Table Talk’, Punch, vol. 25 (1853), p. 10.

[3] ‘Clerical Table-Turners and Spirit-Rappers’, Punch, vol. 25 (1853), p. 266.

[4] ‘Table Turning and True Piety’, Punch, vol. 25 (1853), p. 243.

[5] ‘Clergymen in the Farce of “Turning the Tables”’, Punch, vol. 25 (1853), p. 258.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Aviva Briefel, ‘‘Freaks of Furniture’: The Useless Energy of Haunted Things’, Victorian Studies, 59.2 (2017), 209–34 (p. 210).

[8] Harry Houdini, ‘Daniel Dunglas Home’, A Magician among the Spirits (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 38–49 (p. 39).

[9] William Crookes, ‘Experimental Investigation of a New Force’, Researches in the Phenomena of Spiritualism (1874) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 9–20 (pp. 9, 10).

[10] Richard Kelly, ‘Daniel Home, Mr. Sludge, and a Forgotten Browning Letter’, Studies in Browning and His Circle, 1.2 (1973), 44–49 (p. 49).

[11] Isobel Armstrong, ‘Browning’s Mr. Sludge, ‘The Medium’’, Victorian Poetry, 2.1 (1964), 1–9, (p. 1).

[12] ‘Materialist Malgré Elle’, The Saturday Review, 78.2034, (1894), 436-437.

[13] George and Weedon Grossmith, The Diary of a Nobody (Ware: Wordsworth Classics, 1994), pp. 154, 155.

[14] Florence Marryat, There is No Death (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., Ltd., 1891), p. 1.

[15] Ibid., (p. 222).