Of the more than ten thousand songs published between 1861 and 1865, hundreds dwelt on the topic of death and mourning. Many more songs remained unpublished but circulated in popular repertories nonetheless, and a countless number of these pieces dealt with similar matters.

Across five Aprils, the American Civil War claimed upwards of 650,000 lives, and amassing a total of more than one million casualties. Death left no one untouched; in addition to the soldiers killed, an estimated 50,000 civilians were killed as well. With more than 2% of the population dead, and thousands more injured, the Civil War dramatically changed the nation’s cultural landscape—particularly the ways in which Americans died and grieved.

Called the “singing war,” music played an important role for both the Union and the Confederacy. Music is a performative art, demanding that performers, audience members, and listeners to interact with it. It requires participants to put pen to paper, fingers to string, to open their hearts to the experience, to let the music roll from their tongues. As such, it is a powerful vehicle for remembrance, grief, and sorrow.

Songs dealt with different aspects of sorrow and grief. One particularly poignant song which contemplates battlefield death is called “Brother Green,” or “The Dying Soldier.” It was written by a Union man whose brother was killed in February of 1862 at the Battle of Fort Donelson, and though it primarily is associated with the north, it is also found in southern repertories, with some words changed. The major impetus of the piece is the same in every repertory—a man fallen in battle, seeking comfort from a clergyman, and begging that a letter be written to his wife.

You can listen to a version of “Brother Green” recorded by Hannah Holbrook, playing mountain dulcimer and viola and Benjamin Holbrook playing banjo below:

This song is a quintessential song of the Civil War; the narrator is effectively asking for the creation of a “Good Death” on the battlefield. In her book This Republic of Suffering, Drew Gilpin Faust writes that the “Good Death” of the nineteenth century entailed a readiness to die, a closeness with God, and family present at the deathbed, among other things. The narrator asks for a letter to be written assuring his wife of his faith, and his preparedness for death. Intertwined with themes of religion are threads of nationalism, present in terms like “the southern foe.” Such language declares that his death is not in vain. The letter draws his family near as they are not present at his side, and the verses that describe his relationship with God detail a piety and assuredness.

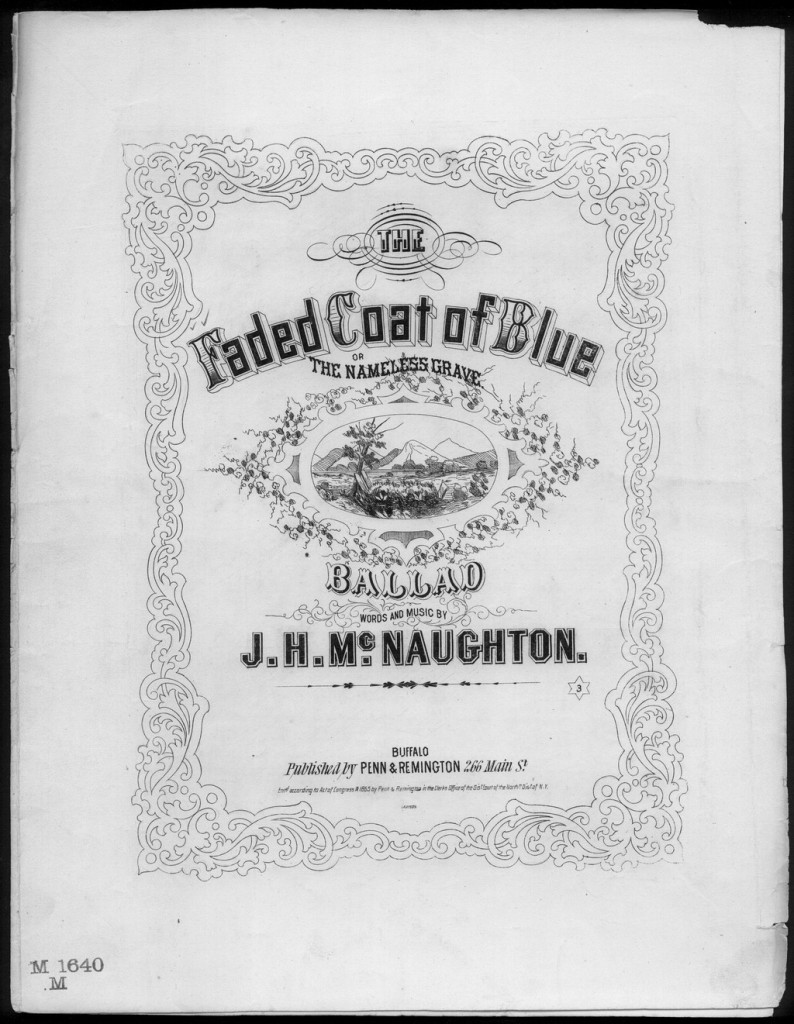

This song was not published as many others were, and, as I mentioned, was written by a soldier directly following his brother’s death in battle, but hundreds of published songs dealt with grief and death, as well. People of all backgrounds published songs during the war, from generals to widows. These songs recounted everything from glorious battlefield deaths, like “Wrap the Flag Around Me, Boys” with the lyrics “wrap the flag around me, boys, to die were far more sweet, with freedom’s starry emblem, boys, to be my winding sheet,” to dour final moments, such as “Faded Coat of Blue,” which includes the lyrics “He cried ‘give me water, and just a little crumb, and my mother she will bless you through all the years to come, and tell my sweet sister so gentle good and true, that I’ll meet her up in heaven in my faded coat of blue’.” These many songs helped Americans cope with uncertainty and unprecedented sorrow, in its many different forms. Every aspect of the war was drenched in grief and violence, and these songs helped civilians and soldiers alike cope with the ongoing trauma experienced during the conflict.

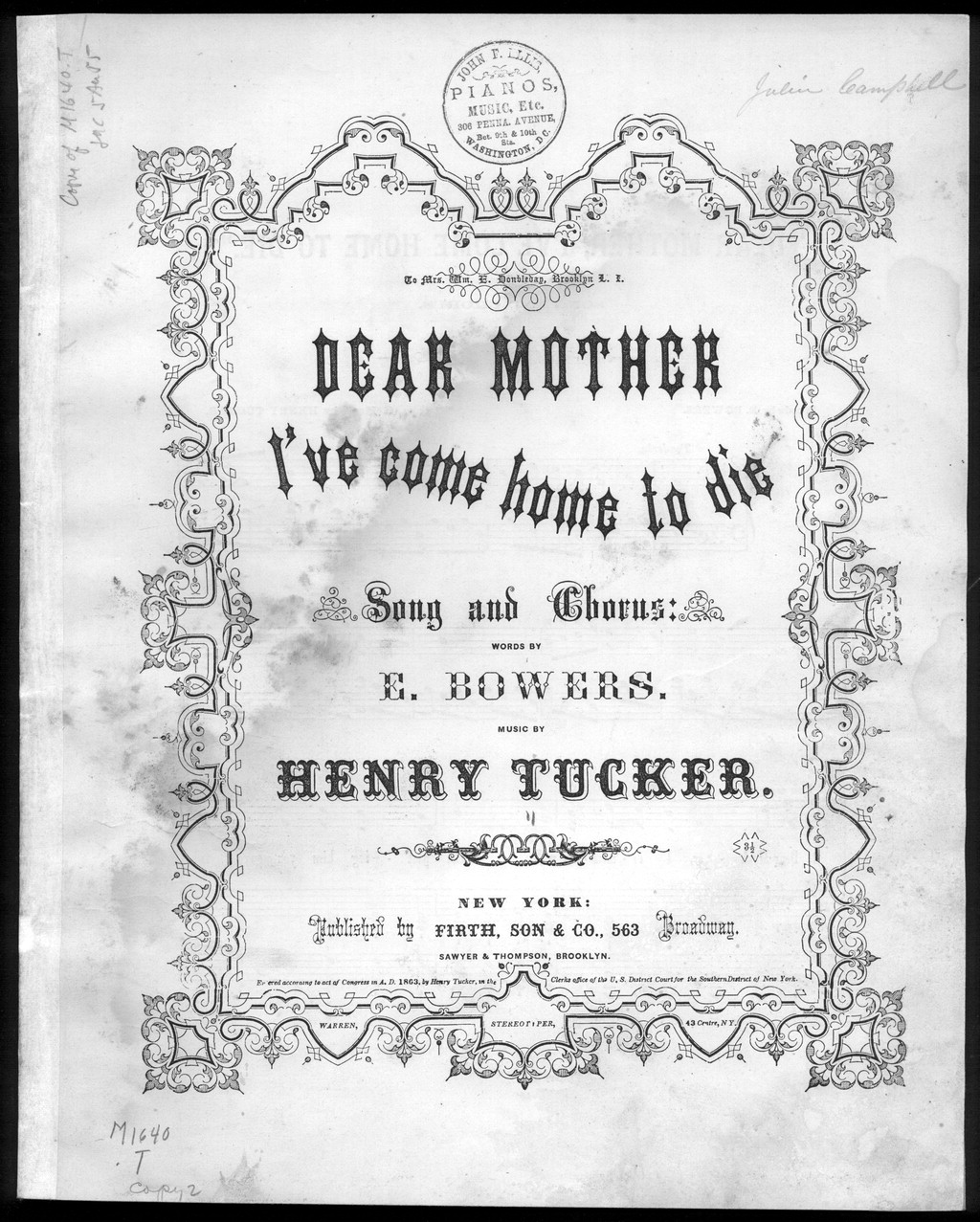

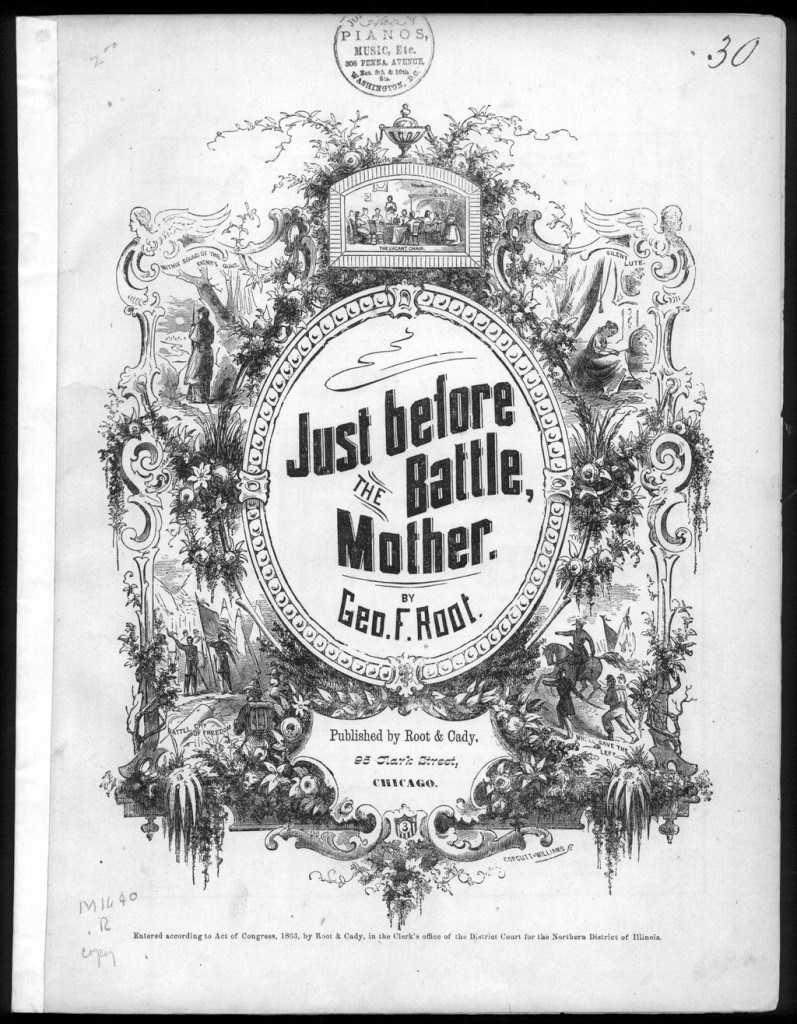

Many songs such as “Just Before the Battle, Mother” and “Dear Mother, I’ve Come Home to Die” were composed from the point of view of soldiers writing to their mothers, seeking comfort and reassuring them of their willingness to fall in battle. I posit that these songs served two very different purposes: first, they helped soldiers retain some connection to their lives before the war, keeping alive the love for those at home—and reminded them to be brave in the face of their mortality; second, they helped the loved ones at home cope with their grief and sadness, and the anxiety of not knowing what was happening with soldiers in the battlefield.

You can listen to a recording of “Just Before the Battle, Mother” with Hannah Holbrook on viola below:

Another notable song written during the Civil War is “The Vacant Chair.” While many songs dwelt on the experience of the war—the inevitability of death, looming mortality, fear of the unknown, unprecedented destruction—this song deals with a death that has already occurred. The song begins, “We shall meet but we shall miss him, there will be one vacant chair; We shall linger to caress him, while we breathe our evening prayer.” The narrator is coping with the loss of a loved one who fell in battle, and goes on to sing:

At our fireside, sad and lonely,

Often will the bosom swell

At remembrance of the story

How our noble Willie fell.

How he strove to bear the banner

Through the thickest of the fight

And uphold our country’s honor

In the strength of manhood’s might.

This verse includes material fairly typical of these wartime songs. Remembering dear Willie as a hero, fighting for the flag, that he fell in battle for the nation. However, the following verse goes on to say:

True, they tell us wreaths of glory

Evermore will deck his brow,

But this soothes the anguish only,

Sweeping o’er our heartstrings now.

The narrator admits here that tales of glory help to deal with grief only so much. The tangible absence of their soldier, his vacant chair at the table an ever-present reminder of what they lost, can not be eliminated by recalling his gallant battle for the nation.

Music is but one art form used to comprehend death, grief, and destruction, but it proved during the American Civil War to be deeply effective. Soldiers and civilians alike sang tunes that helped them face their own mortality and ease their anxieties about death; they sang songs that helped create a Good Death on the battlefield, drawing loved ones and God close; they sang songs that helped soothe their broken hearts when their sons and brothers died, songs that helped them to believe that their deaths were not in vain. Music during the Civil War served many purposes, but ultimately became a medium for comprehending grief and fabricating a Good Death, either from the battlefield or afar. We recall the sorrow of these five Aprils as it echoes down through the decades in lyrics like those found in “The Vacant Chair,”

Sleep today, O early fallen,

In thy green and narrow bed.

Dirges from the pine and cypress

Mingle with the tears we shed.

Hannah Holbrook is a death care professional and independent researcher. She lives in Cleveland, Ohio, USA where she works at DeJohn Funeral Homes and Crematory. Hannah holds a Master of Science in Library and Information Science and a Bachelor of Music in Musicology from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Her research focuses on representations of death, disaster, and mourning in nineteenth-century American folk and popular music, with a focus on the impact of the American Civil War on the nation’s culture of death.

Image Credit: Library of Congress

Audio by kind permission of Hannah and Benjamin Holbrook.