The two years of the title is often cited as the required time for a widow to mourn for her husband – there’s a popular trope that all Victorian widows wore full black with crape veils for two solid years. The reality is much more nuanced, depending on the year and the etiquette authority consulted. This essay will briefly outline the stages of mourning clothing for widows – gradations that were primarily followed by the middle to upper classes, although mourning was aspirational: an 1843 writer noted: ‘The poor like funeral pomp because the rich like it’. In the nineteenth century there was a fascination with the minutiae of fashionable mourning. Just as today’s Wedding Industrial Complex prints lists of expensive ‘traditions,’ so it was with mourning. Articles appeared in newspapers and women’s journals every few months, giving the ideal length of time and proper costume and accessories for each type of loss, suggesting readers’ anxiety about mourning ‘correctly’. Too little mourning disrespected the dead; too much suggested performative grief without real regret. Yet the discussions of fashionable mourning had a valuable function: linking those isolated by bereavement with the season’s latest styles and, vicariously, to a wider social circle. A sorrowing widow could take comfort from the knowledge that she was mourning both correctly and fashionably.

This photograph shows the essential elements of the widow’s wardrobe, also known as ‘widow’s weeds’: the crape—the iconic crinkled fabric of woe–, the veil, and the ruche—which is the white edging on the bonnet. Queen Emma is wearing First, Deep, or Heavy mourning. This stage required fabrics with dull finishes, such as crape or bombazine, which was a silk/wool mix. Gowns and cloaks might be heavily trimmed with crape. No lace, velvet, feathers or ornaments were allowed.

A widow wore a mourning bonnet, sometimes with a white ruche to soften the harshness of black fabric next the skin. A long veil, of either crape or crape-bordered silk, was worn over the face when out of doors, indicating to viewers that the woman behind it was in mourning and should be treated with sympathy.

McCord-Stewart Museum

The long mourning veil was extremely heavy and wearers complained of it dragging their bonnets off the backs of their heads, and of it being stepped on or caught in omnibus doors. Doctors railed against crape veils, claiming that they were both poisonous and depressing. Yet some widows said that they were grateful that the veil protected them from prying eyes and hid their tears.

For indoor wear, the widow’s cap, as we see here worn by Queen Victoria, was essential. These were usually made of fragile fabrics like fine muslin, netting, or tarlatan. Jokes were made about the dainty caps as being ‘too becoming’ or ‘caps of liberty’.

Generally speaking, a widow’s first or deep mourning might last from 1 year (perhaps a year and a day) to 3 years, although some elderly widows chose to wear mourning for the rest of their life. Again, times varied by date, community standards and by which etiquette book was consulted. I have found an 1888 reference which did insist on deep mourning with a crape veil for two full years, but most authorities recommended a shorter and less intense mourning period.

1885-1890, moiré, velvet, satin, lace

National Gallery of Victoria, D74.a-b-1976

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.6441a, b

After the very deepest mourning was past—usually after 6 months–came second mourning. This was also called lightening or slighting one’s mourning. The heaviest crape trim could be removed after 6 months to a year. Some authorities allowed jet trimmings and lace to be added within 3 months; others felt 6-9 months was more fitting. In the later years of the 19th century, after 3-6 months, it was often suggested that the widow add white muslin collars and cuffs to her gowns.

The mourning veil would be shortened to waist-length and made of a lighter silk or wool veiling. Shinier black fabrics, such as moire or taffeta were allowed, as well as jewellery made of pearls or of dark gems like jet or onyx. Second mourning was also worn for what was called ‘complimentary mourning,’ put on for a very short time to show sympathy for a loss by a friend or relative by marriage, such as an 1874 recommendation that a second wife don mourning for a dead first wife’s parents.

Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna’s half-mourning tea gown in grey crape and purple velvet, 1905. The Hermitage

The last stage of formal widow’s mourning was half mourning, worn for 6 weeks to 6 months at the very end of second mourning, to ease out of mourning into fashionable colors. Putting on ordinary fashions immediately after discarding mourning was thought shocking—both to the widow’s alleged sensibilities and those of society. A 1901 etiquette book noted: ‘A sudden transition at the end of the period for mourning from black to glaring colors is in poor taste. Any change…should be gradual’.

Black gave way to dark grey, shading into dove grey, mauve, lavender, or even violet. Black and white, sometimes called Magpie Mourning, was also considered half mourning.

After a year up to 2 years after going into deep mourning a widow could be back in regular clothing. If you were unfortunate enough to have a series of family deaths, it might be years before you were able to wear anything but black.

This was the complaint of a woman in 1877: ‘I missed all my youth…A brother died when I was sixteen, and we went into mourning….Then my father died; next a sister, and another brother, so that…I can remember but one gown I had, between the age of sixteen and thirty-one, that was not black’.

We are fortunate to have a dated sequence of photographs that show mourning progressing from deep mourning to lighter.

McCord-Stewart Museum

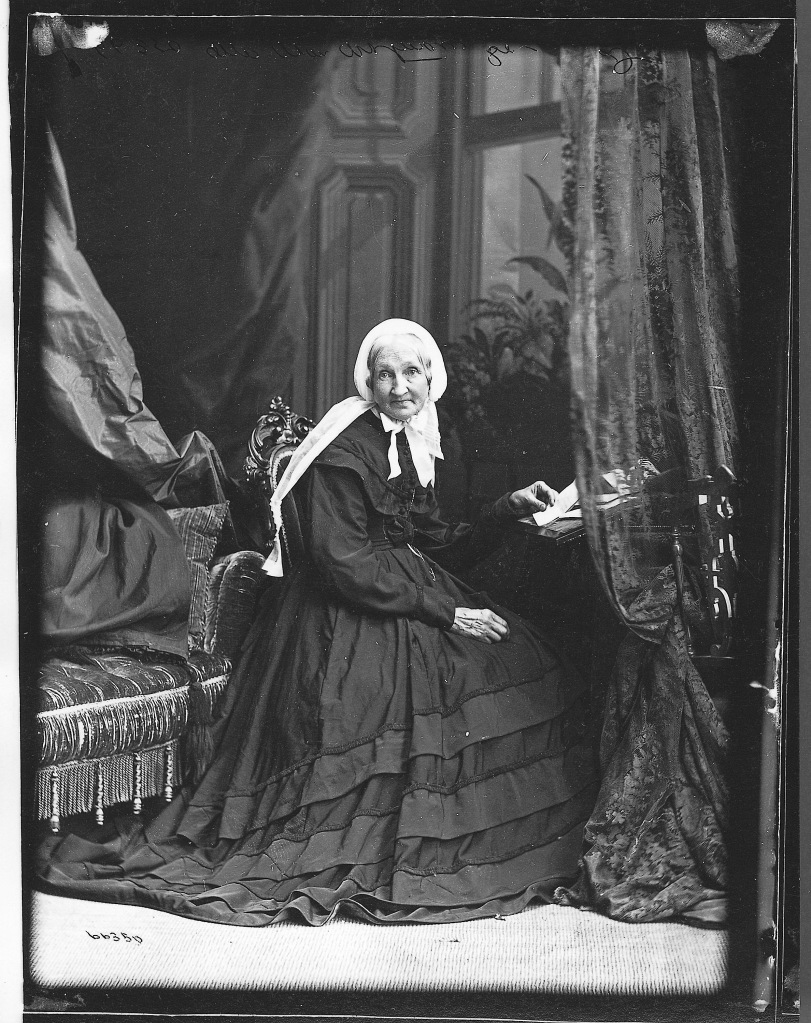

This is Mrs William Notman Senior in deep mourning for her husband, who died in December of 1867, photographed by her son, William Notman in January 1868. Her skirt is nearly covered up to the waist by crape, and there are heavy trimmings of crape on her sleeves and bodice.

McCord-Stewart Museum

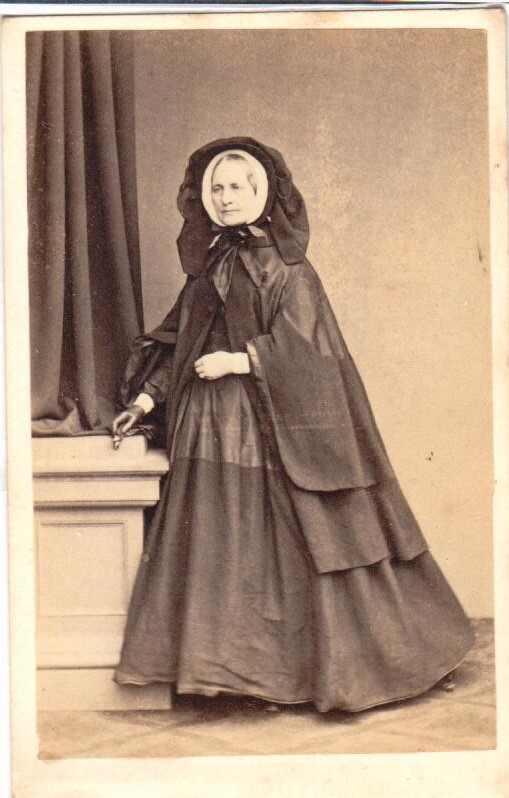

In 1869, the skirt has a narrower crape border and a few shoulder trimmings of crape. She wears a widow’s cap with long lappets.

McCord-Stewart Museum

Four years after her husband’s death Mrs Notman wears a black gown and her widow’s cap, but the only crape visible is in the narrow bands of ruched crape on skirt, cuff, and bodice yoke.

Victorian and Edwardian photographs show not only conventional mourning, but also much more variety than was perhaps approved by the etiquette books: we might see beadwork and shiny fabrics worn with the long crape mourning veils of first mourning. We cannot tell whether a merry widow was simply pushing the boundaries of second mourning or if the wearers were actually criticized for these grave sins against propriety.

Victorian mourning did not die with Queen Victoria in 1901; it took the mass casualties of the Great War to kill it. There were grass roots campaigns during the War against deep mourning, due to the expense and the deadening effect it had on morale. It was suggested that an old-fashioned jet brooch or a black arm band be substituted. In consequence, full-crape mourning went out of fashion after the First World War, eventually worn primarily by royalty and film stars.

Personal Collection.

The Victorian emphasis on the stages of mourning was not just some morbid social construct; it had the purpose of working through stages of grief. I’ve been saying for years that we need a universally recognized mourning symbol—an arm band or a piece of jewelry–to show the public that someone has suffered a loss and should be treated with care, not told to ‘get over it’ in a few weeks.

Today the bereaved are told not to make any dramatic changes in the first year after a death, corresponding to the Victorian notion of deep mourning and limited social obligations for a year. This makes perfect sense in the light of the disorientation found in that first year. Second mourning and Half mourning followed similar paths to a time when one’s grief was perhaps less acute and those who had suffered a loss were ready to resume both their fashionable dress and their place in society once more.

Further Reading

A is for Arsenic: An ABC of Victorian Death, Chris Woodyard, 2023. Appendix on mourning stages/times 1837-1918

Taylor, Lou. Mourning Dress: A Costume and Social History. London, UK: G. Allen and Unwin, 1983.

Cunnington, Phillis and Catherine Lucas. Costume for Births, Marriages & Deaths. New York, New York: Harper & Row: 1972.

Curl, James Stevens. The Victorian Celebration of Death. Stroud, UK:Sutton Pub., 2000.

Helen Frisby. Traditions of Death and Burial. Oxford, UK: Shire Publications, 2019.

Jalland, Patricia. Death in the Victorian Family. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Morley, John. Death, Heaven, and the Victorians. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1971. Woodyard, Chris. The Victorian Book of the Dead. Dayton, OH: Kestrel Publications, 2014.

Chris Woodyard is an Ohio-based historian of death and the supernatural, author of A is for Arsenic: An ABC of Victorian Death and The Victorian Book of the Dead.